In this episode of K9 Conservationists, Kayla and Charles speak with Kyoko Johnson about her work at Conservation Dogs Hawaii.

Weekly suggestion: Remember to take the plunge. Apply for that puppy, launch that business, sign up for the new class.

Call to action: Review us on Apple podcasts!

What are some threats that Hawaii is facing?

- Hawaii is in the middle of the pacific ocean. One of the major principles of conservation is island biology, which is how species and organisms are not able to easily get there from other places

- It cannot be “fixed” by just allowing other species to arrive, as they would be considered invasive species and the island is much more sensitive to those

Is there anything unique about Hawaii’s wetlands?

- There are some unique wetlands due to orographic rainfall from the volcanic activity

- Because there is a lot of water and a lot of sun, it’s so quick for invasive plants to take over

- 80% of the coastal wetlands were lost due to development

Why are invasive species so dangerous to Hawaii?

- The island struggles more than other places with invasive species

- On the plus side, it can be easier to square off invasive species and make safe zones

Mentioned in this Episode:

- The photo contest where CDH’s photo won third place

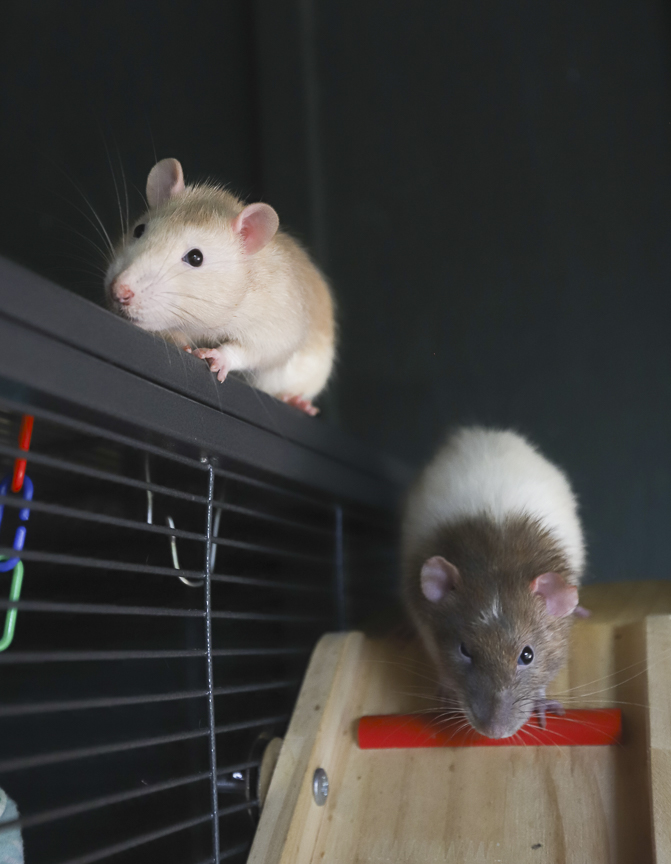

- Kyoko’s rats in motor trucks and more – see photos below

Where to find Kyoko: Website | Instagram | Facebook

Where to find Charles: Website | Twitter | Instagram | Nature Guys

You can support the K9 Conservationists Podcast by joining our Patreon at patreon.com/k9conservationists.

K9 Conservationists Website | Merch | Support Our Work | Facebook | Instagram | TikTok

Transcript of Conservation Dogs of Hawaii K9 Conservationists Episode

SPEAKERS

Kyoko Johnson, Charles Van Rees, Kayla Fratt (KF)

Kayla Fratt (KF) 00:08

Hello and welcome to the canine conservationist podcast where we’re positively obsessed with conservation detection dogs. Join us every week to discuss ecology, odor dynamics, dog behavior and everything in between. I’m your host, Kayla Fratt. And I run canine conservationists, where I trained dogs to detect data for researchers, agencies and NGOs. I’m super excited to share today’s interview with you. But first, we’re going to talk about our weekly suggestion. This week, let’s remember to take the plunge, apply to buy that puppy, launch that business or sign up for that new class. Hey, everyone, I just wanted to let you know that we had some audio issues with this episode, both Kyoko and Charles had to rerecord some of their answers. So if the audio sounds off, or things sound a little bit awkward, that is why it’s still a really great interview and bear with us. Thanks for understanding. Today I’m joined by our conservation correspondent Dr. Charles van Rees. Hello. To interview Kyoko Johnson of conservation dogs of Hawaii. Hi. So, as a quick intro for Kyoko, she’s been training dogs and their people in Hawaii since 2008. Her love of dogs came from volunteering for various dog rescue organizations and shelters on the island. And since beginning her dog training career, she’s earned various professional training and instructor certifications, including through the CCPD, the KPA and the NACSW and we will have all of those acronyms in our show notes if you’re not familiar with what they are. Kyoko began her career as an ecological scent detection dog trainer and handler in 2012 through allaahu wind farms, habitat conservation programs, which utilized canines to locate endangered sea bird and bat fatalities to measure the environmental impact. She went on to train and handle dogs for various conservation projects, including a study at Hanalei National Wildlife Refuge, which measured the efficacy of using conservation detection dogs to lower avian botulism related mortality, and collo Maoli. I’m so sorry. I’m the one here who should not be pronouncing Hawaiian words, which is an endangered Hawaiian duck. And the projects that use utilize the dogs to monitor eradication efforts of invasive yellow crazy ants, which is a species that caused great harm to seabirds at Johnson atoll National Wildlife Refuge, Kyoko continues to operate her private business business Country Canine LLC, in addition to serving as the president and lead canine trainer of conservation dogs of Hawaii. So thank you so much for joining us, Charles, why don’t you kick us off with our first couple of questions.

Charles Van Rees 02:37

My first question Kyoko, first of all welcome and aloha. And then thanks so much for joining us. It’s great to have you on the show. And I’ve as soon as I heard this was happening, I was really interested in being involved. I am especially interested, of course in your work going on at Hanalei National Wildlife Refuge, which is a place very dear to my heart. And I guess I wanted to start off sort of just by asking, What do you guys up to in Hanalei and elsewhere? What are sort of the current comings and goings of conservation dogs Hawaii?

Kyoko Johnson 03:08

Sure. So I just got back from Hanalei, actually working with a few of the dog handlers there. As you know, we had conducted a study there several years ago, to measure the efficacy of the detection dogs. And so the canine program that I helped set up this past year was based on the study, like the lessons learned, and all that stuff. So right now they have three dog handler teams that are certified, what we call level one, where they’re searching for targets that are, you know, physically accessible to the dogs on the dikes and in the ditches and stuff like that. And we they’re conducting surveys right now doing quite well. And they’re also training for level two, which will involve the dogs you know, alerting from a distance at targets that are not accessible to them that are located inside the taro units. So yeah, so the refuge is kind of a unique environment that it’s a mix of managed wetland units as well as farmed taro or kalo units. So you know, we they don’t want the dogs tromping all over the plants and damaging the crops. So you know, we circumnavigate them. And eventually, we’ll have the dogs go into, yeah, but the taro to pinpoint targets.

Charles Van Rees 04:32

And those targets those are bird corpses or bird crops, specifically with botulism or what’s the

Kyoko Johnson 04:39

So the general goal is to curb or prevent, you know, the outbreak of avian botulism, but we’re having the dogs trained and finding all carcasses of waterbirds just because they you know, any carcass whether they have botulism or not can you know, trigger an outbreak in protein source. Yeah.

Charles Van Rees 05:03

Right. Wow. And I imagine it’s that’s for all these listed species, any carcass might be of interest, right? If people are doing studies on mortality rates and causes of mortality and things like that if you can, if you can get more more bodies as it were for that, that sounds like that would be informative, even if you weren’t directly preventing the outbreaks. In my work with them, that’s a big problem is you just don’t know where anything is in these wetlands. Right. So that’s a good place for dog noses.

Kyoko Johnson 05:34

Yeah, so that’s what we’re doing in Hanalei. And as far apart as our other projects, I’ll just give you a quick overview. You know, one of our main programs is the invasive plant program with devil weed or Cremona. odorata. Yeah. And so we have five operational dog handler teams conducting surveys. We started that a couple of years ago, and it’s going really well. It was definitely a learning process. I can talk to you more about it later. But yeah, so they’re out conducting surveys. We just hosted a big plant pulling event recently, that didn’t involve the dogs, but our dog teams found some crazy infestation sites. So we recruited a bunch of Marines and, you know, conservation people to pull like 4000 plus plants. Yeah, and then our rodent mongoose detection is on hold. Our goal is to do biosecurity, like screening boats that go out to the remote atolls and wildlife refuges. Yeah, so that’s a big goal. But right now we’re doing more behind the scenes work, like working on presentations for potential partners and things like that. Yeah. And then while Yeah, the CBRE work is really exciting. We just started that this year, and we hope to do a lot more of it next year. So that’s kind of we’re training for it, but not actively in the field, because it’s not the right season right now.

Charles Van Rees 06:58

Plenty of irons in the fire, then gosh, yeah.

Kayla Fratt (KF) 07:02

Yeah, it sounds like you’ve got got tons of free time. Right? Yeah. Well, and that actually leads us into my next question really nicely. So you mentioned you’ve got kind of level one and level two for the dog accreditations or certifications. And I know one of the things that’s really unique about the program you’re running is that you do work with some volunteers. So can you tell us a little bit about kind of how you find those volunteers how you screen and train them? I know, that’s something that it just seems like a massive logistical endeavor. And I know I’ve heard other conservation dog handlers being very skittish about kind of the concept of volunteers in this line of work.

Kyoko Johnson 07:42

Yeah, yeah, I understand their concerns. I can address some of those later. Would you like to hear about Hanalei? Or about the devil weed program? Or little of both?

Kayla Fratt (KF) 07:53

I guess a little bit of both, how different are they?

Kyoko Johnson 07:56

So the Hanalei program is that they’re not actually our volunteers. They’re US Fish and Wildlife volunteers for the refuge itself. So I’m being hired or our organization was hired to do the training and development of that program. The fact that they’re volunteers is, you know, or not paid, I should say is, you know, kind of not important, I don’t think because it’s more about finding the right people and the right dogs that work for that application. And the people who have the background with the water birds, like all volunteers at Hanalei are required to have at least, you know, several months of experience doing visual botulism surveys before they can, you know, participate in the canine program, in addition to having the criteria to meet the canine handler team criteria. So yeah, so they, the volunteers at Hanalei are required to have experience with the water birds like knowing how to read their behaviors, how to, you know, avoid bug, you know, causing any disturbance as much as possible, knowing what the nesting season is, and you know, what behaviors, they display, that kind of thing. And then in addition to that, we have a checklist of, you know, qualities that we’re looking for in the dogs and handlers and unlike, you know, maybe like an off leash, vast landscape survey for scat or something like that. You may not want to use a dog at the refuge who is, you know, extremely. Not that you don’t want them to be high drive, but you don’t want them you know, running around like crazy and disturbing the wildlife so, you know, we’re looking for dogs that are a little bit mellower, who still have the drive to work and do what we need them to do, and who are not going to be at all bothered by the tons of birds that are all over the refuge. And then as far as the devil weed program, it’s actually probably I would say the opposite, you know, it’s all off leash work. You know, we’re not working around sensitive wildlife. So we’re looking for dogs that have pretty high level of drive. And in fact, you know, I didn’t expect the devil weed project to require that so much but we learned from working with this particular plant in these environments that it really does require that much drive because I think Kayla, you’ve worked with plant detection as well and you’ve seen that it’s not always that easy to pinpoint, like it is a bird carcass or something like that. So with the variable, you know, weather conditions and stuff like that, you know, the obstacles, the bushes and things that they have to get around, it does, you know, require that kind of drive in the dog. So we seek out not only dogs like that, but handlers who are already, you know, active outdoors, and it’s not like something that they have to train towards. Yeah, because I have had, you know, potential dog handlers get really mad at me, because they, you know, did try to do a survey and they’re like, that almost killed me. You know, it’s even though it’s, it wasn’t that challenging. So, yeah, we definitely look for people who are physically fit and already are outdoors doing that type of thing with their dog on not detection, but you know, hiking and rough terrain and stuff like that.

Kayla Fratt (KF) 11:22

Yeah, thanks so much for that answer, Kyoko. So it sounds like you’re looking for definitely making sure that you’ve got kind of the right dog for the job. And I’d love to dig into that a little bit later, if we’ve got time. You know, as far as the the difficulties of working with plants, and kind of finding the dog who’s got the right drive level. And then also looking at making sure the humans have the right fitness. What are some of the other things that you’re looking for, as you’re screening volunteers for these for these positions?

Kyoko Johnson 11:46

Sure. So for the devil week program, we, it’s required that all dog handlers have at least a year or more of scent detection training experience, including odor and printing, because we’re a small organization, we don’t have a huge amount of funding, and we don’t have a facility. So we’re not able to, you know, we don’t have the resources to train completely green teams. So we do require that previous experience, whether it’s, you know, search and rescue or nosework classes, or, you know, bomb detection, or whatever it is. So just to give you a little background on why the devil weed work requires a high drive dog, we found that the wild plants are sometimes really hard for the dog to pinpoint, especially the smaller plants, because the pooling odor in the environment is stronger than the source odor. Sometimes a dog will catch odor, and then go right to a nearby plant. And it’s easy, but oftentimes, the dog has to keep searching and searching after it catches odor for you know, 10 plus minutes to locate a tiny plant, and they can’t give up until they find the plant. So that’s not easy. And then there are situations, particularly on windy days when the dog catches odor from as far as 80 meters away. But in order to get to the plant, the dog has to navigate around, you know, super thick vegetation and other obstacles or go down steep slopes and deal with wind direction switches. So yeah, the teaching the dog the odor is easy, but the actual field work for devil weed turned out to be more challenging, especially now that these dogs are really sensitive to the odor, and they’re finding tiny plants and plants that are really far away. And some things that we don’t require, you know, ahead of time is more just, you know, a really good understanding of environmental conditions and how they affect, you know, odor and stuff like that. I mean, we they need to have the basics, as far as whatever their background was. But working in, you know, a large outdoor environment is is quite different from, you know, maybe we’re doing bomb detection indoors or nose work or something like that. So that’s something that I work on with the handlers teach them. I shadowed them in the field a lot before their operational, you know, learning about GPS devices and data submission and record keeping things like that, that they might not be used to, we go over that kind of stuff, which is a little bit easier than teaching them about, you know, just how to be outdoors and how to work with your dog and stuff like that.

Charles Van Rees 14:24

Yeah, useful skills. I mean, it sounds like you know what I mean? Like they’re coming out of that with a lot.

Kyoko Johnson 14:30

I hope so my goal is to not just have them be, you know, dog handlers for this particular program, but to groom them so that they can do additional jobs in the future. Because as you know, our organization’s goal is to spread the use of, you know, effective use of conservation dogs in the Hawaiian Islands and maybe even beyond. So I’d love to have more people trained up to do this kind of work. It’s hard to import people from the mainland or we’re so isolated. Yeah. You know, it’s hard to get here. You can’t bring your dogs here that easily. So yeah, I think to build local capacity is very important.

Kayla Fratt (KF) 15:08

Yeah, that makes a ton of sense. And it reminds me I know, there’s been some, some white papers put out by working dogs for conservation and others, especially on international projects that often, like trying to get a conservation dog program up and running in a lot of other countries, is cost prohibitive if you’re importing the handlers, but if you’re able to kind of get the teams up and running on the ground, locally, that can make these programs just that much more feasible.

Charles Van Rees 15:33

Wow, that’s really smart. And I like that, for me, at least coming from the conservation field, especially on the international side of it. You know, there’s such an emphasis in the last decade of changing conservation to be more local, to be more involved with the context around which this conservation is happening. For a number of reasons, right, but you know, ethically speaking, of course, it makes so much more sense to just involve local people, because you’re empowering the communities, you’re cutting away at this sort of conservation imperialism that happens so often. So I love that idea. And I think it’s absolutely fantastic. You guys are doing it. So I mean, I have little to say other than, like, kudos. And wow, that’s amazing. And thank you for doing that.

Kyoko Johnson 16:16

Yeah, one other thing that I’ve found with using or training volunteer dog handler teams from the community is that it’s, it’s great for PR, and for just spreading the word about the conservation causes, because the people are more interested in hearing about, you know, community members doing this rather than Oh, just some professionals out there that they can’t relate to. Right. Good thing as well, although there are, of course, negative perceptions of volunteer dog handler teams as well.

Kayla Fratt (KF) 16:47

Yeah, yeah. If you want to talk about that a little bit. I mean, one of the other things that I’m thinking about, and then I will let you get to some of the perceptions of volunteers is, I know, I talked to a lot of people who want to try this field who want to experiment or learn about conservation dog work and try it out, but maybe aren’t willing to do or aren’t able, for whatever reason to do it kind of full time or do it you know, the way I’m doing it, where I live in a van and I drive from field site to field site, and I don’t have, I don’t have property, I don’t even have a storage unit I have no, like my mailing address is a disaster. And most people don’t want to do that. And a lot of people aren’t in a position to do that. So I really love that it gives people this ability to try out this field at a really high professional level, it seems like you’re offering a ton of mentorship, a ton of oversight, right. And again, it makes it much more accessible to local people, rather than just these kind of elite vagabonds who move around in charge, you know, we charge through the nose, when we have to come to you and do this full time. So yeah, what are some of the the negative perceptions or kind of things that you’d like to address as far as volunteer work?

Kyoko Johnson 17:59

Sure, yeah, I think one of them is that, you know, I think you touched on that, but the fact that volunteers are, you know, low skill level, and it lowers the image of dog handlers and dog trainers in this field. And I think that can happen with you know, hobbyist type people who just wing it and try it on their own. And they, they maybe have not been mentored by professional, but, you know, our goal is to train people professionally, and to have them meet a certain standard and pass certifications or, you know, to certain criteria before they become operational, so that they can meet the goals that we have. So, yeah, I think that, you know, the level of skill really just depends on whether the volunteer is trained by a professional or not. And I think the same is true with paid handlers as well. You know, because I’ve worked with paid handlers who don’t necessarily have the best attitude, and they just do the minimum to get paid. And they’re not eager to learn, and they don’t necessarily meet the criteria, either. So yeah, I think whether they’re paid or not, I think it’s not so much the issue as yeah, the mentorship they receive and the criteria that they’re asked to meet. Yeah. And then the other negative perception is money, money related. I think there’s the perception that, you know, if there’s free volunteer dog handlers out there, then the professionals or the, you know, the skilled people are not going to get paid, like they’re taking the money away from, you know, and I think that’s true with other fields as well, but I feel like in conservation, I mean, it’s so much supported by volunteers, you know, at Honolulu, or, you know, I lived for several months. I mean, there are tons of interns, there are tons of volunteers supporting the refuge and you know, the staff was almost like a small part of it. And everybody we’re just is hard and they were in it for the cause. So I feel like you know, maybe they don’t have volunteers in, you know, police dog work or, you know, TSA work or something like that. But for there to be volunteers in the conservation field seems like a natural extension, just because that field itself is like,

Charles Van Rees 20:19

A wash in volunteers.

Kayla Fratt (KF) 20:21

Yeah. Well, in my experience, on the volunteer end of things, I used to volunteer at a raptor rehab center in Missoula, and I volunteered at a couple different animal shelters. And in both cases, I think I was mostly filling in a gap that was needed, but they didn’t have the budget for otherwise, like, the Raptor rehab center, I used to work volunteer at the only paid staff member was the CEO who lived on site and took care of the birds 24/7. And they didn’t have you know, that had zero budget for anything else. And especially, you know, circling back to Hawaii being so remote, it makes a ton of sense to have people on the ground. And I guess I’m not 100% sure, but it seems like the work that you’re doing wouldn’t necessarily, it’s not like you could replace three or four volunteers with one full time person and pay them even if you have the budget to do that. Right. Like logistically speaking.

Kyoko Johnson 21:16

Yeah. So yeah, I agree with that. And I also feel like that, you know, because we don’t have many qualified, skilled handlers here at the moment. Other than a few handlers who work for the wind farm, maybe or for TSA, it is important to, you know, start out well, it helps to start out with volunteers, and then eventually, we can pay them, you know, because there’ll be more jobs eventually, after, you know, we prove ourselves a little bit with the work that we’re doing. So I feel like, you know, we’re developing the field, including for paid jobs as well.

Kayla Fratt (KF) 21:55

Yeah, yeah, that definitely makes a lot of sense that I know, when I was even first starting out in freelance writing, the way I got a couple of my first clients was that I offered to write two or three blog posts for free. And sometimes I even emailed them with a blog post I had already written, and said, hey, you can post this for free, I’ll write a couple more for you and eventually, we can talk about you paying me and so even outside, you know, and that’s in a very, for profit oriented part of the world. But it’s not unusual to use that as a strategy to prove your worth and get your foot in the door.

Charles Van Rees 22:25

And certainly for the entire field, right? I mean, nobody knows about conservation dogs, period. Nobody knows.

Kayla Fratt (KF) 22:32

That’s what we’re trying to fix.

Charles Van Rees 22:33

That’s why it’s so great that we’re here and it’s so great. What Kyoko is doing but like to be frank, right? It’s as far as most conservation biologists that I’ve ever run into and most of my colleagues go, you know, people have either never heard of it, or think it’s really neat, but it doesn’t apply to them. Or they have no idea whether it’s a proven thing to begin with and so I think I think Kyoko is absolutely right, that what you are doing is gradually establishing the demand for it right, scientifically, in the scientific community is a very different one as Kayla recognized, and then a for profit community. And so there’s a different sort of culture that you’re grappling with and doing that but I think that the work that the conservation dogs have is doing is exactly what needs to be happening, those sorts of really high visibility sort of cases. And, you know, Hawaii is a major, a lot of conservationists are looking at Hawaii, right. It’s it’s up on a stage in a lot of sense. It’s the Endangered Species capital of the United States. And so I think it’s a yeah, these are very high visibility issues, high visibility cases that if people can see this relevance, I think that’s going to build momentum a lot faster in the scientific community.

Kayla Fratt (KF) 23:46

And that actually pivots us really nicely, Charles, once again, Well done everyone with the pivot. Let’s talk a little bit about why Hawaii is so important and interesting ecologically, and some of the threats that Hawaii is facing, you know, so we can talk as our conservation correspondent tell us a little bit about it.

Charles Van Rees 24:05

Okay, yeah. I mean, Kyoko has been installed in this for longer than I have. So I will readily defer to her on any, any other anything she has, and certainly shifts things to add, please don’t hesitate to butt in, I guess, to be very, very quick and dirty about it. Hawaii is so ecologically interesting, because of its geographic location, really. I mean, it is in the middle of absolute nowhere. To be very blunt about it, right? We have it’s the most isolated archipelago in the world in the absolute middle of the Pacific Ocean. And one of the first things that people learn in ecology and evolution is this is well, yeah, one of the major principles is this idea of island biogeography with which without being too fancy, and cut technical about it is essentially saying, right, if if living organisms can’t get someplace, or if it’s harder to get to that place, because it’s some form of island, maybe it’s an island of forest in the middle of a giant plane, or an island of water in the middle of a very dry area. It’s a type of habitat that is not surrounded by itself, right? And it’s somewhat isolated, that makes it harder to get there, which means that fewer things get there. And then you know, what we’d consider, I don’t know, sort of a normal continental ecosystem does not really happen. And oftentimes, really weird stuff happens on islands and weird mix, especially weird stuff happened on Hawaii, because a lot of the species that we expect to be filling the those ecological niches right, or those specific functions and ecosystem are not there. So that weird stuff happens. And you get these very strange systems. So in Hawaii, before the Polynesians arrived, right, all of the large land animals were huge ducks primarily that did all sorts of weird stuff and they were they were the major grazers and herbivores and whatever else, and that’s really weird. And they were they were no amphibians, there were no reptiles. There were no ants. The only land, quote unquote, land mammal was a are mammals were a one species of bat and one species of seal, which I guess you know, it flops up on the land once in a while, I guess that counts as a land mammal to some extent. Because all these things couldn’t get there. Right? So then you get this totally whacked out system. And the problem is that if you if you kind of change that filter and allow things to reach that island, then that were never there in the past, what we would term invasive species. They are the island is much more sensitive to those. There’s an oscillating system.

Kayla Fratt (KF) 26:36

Would that almost be like an immunocompromised kid? Or like someone who’s like never been outside? Never been exposed to dirt? And then, like somebody who lives like an ultra high genic life is much more susceptible to infection? Would that be an analogy that makes some amount of sense?

Charles Van Rees 26:51

Yeah, I think, I think if you like get down to the specifics of immune systems, maybe less so. But yeah, like the idea of doctors Yeah, but they haven’t been they haven’t, right. So like, the wildlife of Hawaii has not been exposed to ants, until people introduced a bunch of ants. And then that caused a ton of problems, right? Because ants are a major thing. And they occupy a big niche that way. So you can compare it to like people who haven’t been exposed to smallpox suddenly getting smallpox, right? And it kills a ton of people. It’s one of those things where it’s, it’s not in your ecological, recent ecological history. And so you’re kind of as an ecosystem not prepared for it. Probably not explain that particularly well. But but the idea being that what makes Hawaii so weird and so unique and so interesting, is also the same thing that makes it so endangered, because everything that developed in the Hawaiian Islands, and there’s so much endemism, and so much stuff that’s found nowhere else. And it’s all super, super weird. Like they have carnivorous caterpillars, like come on. That’s all coming from that the reason it’s so weird is the same reason why it can’t work with wildlife from elsewhere. And it’s so much easier to invade. You could think of it like trying to like fit people onto an elevator. And if you go into like continental tropics, that elevators crowded with species, in some place, like Hawaii is like maybe five people in the elevator doing a whole bunch of different things. And you could easily shove much more people in there. And they can, you know, really take over. So obviously, we’re struggling for good analogies here. But yeah, that’s

Kayla Fratt (KF) 28:25

Friday at 8pm. You’re okay.

Charles Van Rees 28:28

But I think that’s that’s my quickest way of saying it. And I would definitely encourage people to watch documentaries, check out some books on Hawaiian natural history, because it is zany. And this does apply to all sorts of other islands. But I don’t think it’s ever been as bad as it has been on. I shouldn’t say bad as interesting as has been in Hawaii, because it’s so so isolated.

Kayla Fratt (KF) 28:50

Excellent. Yeah, that makes a lot of sense. And is there anything in particular because I know Hanalei and where Kyoko has worked and then where you’ve done your PhD work as well are both kind of centered around wetlands. Is there anything unique with Hawaii’s wetlands as well that we need to be thinking about?

Charles Van Rees 29:06

That’s an awesome question, considering, you know, we’re already starting with a weird ecological system here being weighed out on these islands. And I think you’re tremendously astute to be to be asking specifically about the wetlands. Wetlands themselves are, of course, very different ecosystems, you know, compared to forests, and grasslands, and things like that, they are so intensely tied to hydrology, the way that water arrives in the landscape and how it moves through that it can cause them to be very, very different between regions. So in Hawaii, again, we’re on an island in the middle of the ocean. Water does weird stuff there and that affects, of course, how these how these wetlands are made, formed and maintained. It actually kind of depends on the age of the island. So we know that these islands are all volcanic that they are that they are forming from magma coming up through these the continental plates or that the Earth’s crust basically. And as as that plate is moving, right, more islands are kind of being sort of pooped up out of it. And the older the islands are, the more this the shorter and kind of more they settle on themselves, the volcanic material. But that causes this very abrupt increase in elevation going straight up from, you know, zero elevation, the level of the ocean, which tends to intercept moisture, like bodies of moisture in the air clouds might be an easy way to describe that, that are that are moving along the ocean, those get pushed up by running into that land. And as they get pushed up, they cool down, they condense. And of course, you get rainfall. So we call it orthographic rainfall made by the Earth or the rock. And so these the taller Hawaiian Islands, which are the younger ones, can pull down a lot more of this of this water. In general, though, you’re getting pretty much from all the main islands, which are relatively young at big, they’re still above the water. They’re pulling down a lot of this rainfall. So there’s a lot of rainfall happening in the mountains. And again, because they’re volcanic, you’re getting these sort of volcanic dikes, certain densities of rock that actually almost act like pipelines, essentially, that allow the water to drain, very deep down into the into the island. It’s more permeable that way than a lot of continental landforms. And that causes this huge upwelling, then, of water coming basically up from under the ground along the coastline and the what they call the coastal plain. And some of these middle aged islands like Oahu and Kauai, where a lot of these wetlands are and a lot of these wetland dependent organisms are, you have really, really steep mountains because of the erosion and a really, really flat, lush coastal plain where everybody likes to hang out and have their, you know, surfer shacks or whatever, and we’re Honolulu and stuff is now and on those coastal plains because of this upwelling of water, you get these tremendous wetlands that that formed, a lot of them had been lost on on Oahu, especially Waikiki Beach, actually, which is, you know, just gigantic, very famous tourist beach. None of that sand is original that used to be a massive freshwater wetland fed by a spring. My understanding is that Vikki key via means fresh water. In Hawaiian in Vikki key was referring to water that was like bouncing around or coming up in a spring and so that that whole giant wetland complex was was springfed. So it’s a very particular type of wetland that tends to develop in Hawaii. And there are other types of wetlands like on Kawaii up in the mountains, there are areas that even though they’re on a slope, it literally never stops raining, wettest place on earth kind of thing. And those areas will have their own sorts of wetlands. But the ones that we’re concerned about with the Hawaiian water birds and where the birds from conservation dogs Hawaii are working. Those are these these low elevation, flat wetlands, just beautiful, clean, fresh water coming up from the ground. And unfortunately, they’re very vulnerable. Just like any other ecosystem in Hawaii, they’re very vulnerable to invasive species. And wetland ecosystems, because there’s a lot of water and a lot of sun are really great for aggressively invasive plants. So there are a number of invasive emergent plant species that can just take over these wetlands so fast. So I was doing a lot of work with the Fish and Wildlife Service in Hawaii dofaw, the Department of Fisheries and Wildlife or something like that, when I was over there, and the amount of maintenance they had to do to maintain habitats for these birds was absolutely tremendous if they stopped mowing or burning or what have you. Every couple weeks to months, these these wetlands would be overgrown in no time and all the nesting habitat for these birds was gone. So it’s really, it’s not the way we think of invasive species on on the mainland, for example, these things are so aggressive and can push through so quickly the management has to be really continuous. And as we talked about being the usual suspects of invasive mammalian predators are also a big threat here as they are to the forest ecosystems. But yeah, in my mind, those are sort of the things that make these wetlands different and sort of the the main threats that they’re faced with of course the the other thing that you that we just can’t deny which is less threatened now, but it’s part of the reason we’re in this situation where these where these remaining wetlands are in such bad shape is we just lost a lot of it. That was that was some of the first work I ever did in my PhD, looking at the habitat that these waterbirds especially are found in on the island of Oahu, we’re dealing with in terms of low elevation wetland loss, probably 80% or more of the coastal wetlands were lost to development because they were nice places to build, right? You have a view of the ocean, you have nice flat soil, good for agriculture, whatever. Those areas very quickly came under threat of development. So the remaining ones are in tiny little pockets that we managed to protect. And they’re so so precious. But by dint of being so low in their coverage, right, they kind of that that fragments, the populations of these of the organisms that rely on them.

Kayla Fratt (KF) 35:44

Yeah, that makes a lot of sense. Thank you for giving a lot of that context. So coming back to you Kyoko, can we talk a little bit about some of the interesting places you’ve worked? I think when most people think of Hawaii, myself included having never been there, I think of beaches, palm trees, I’m aware of the Nepali coast. Yeah, that’s a place I know I want to go. So I’m aware that there are mountains, volcanoes and forest. But I know like, for example, you just a photo from conservation dogs, Hawaii just won a photo contest. And it was not something that I was expecting to see from Hawaii. So why don’t you talk a little bit about some of the places you’ve worked, and some of the diversity that you’ve seen there? And maybe if you want to also speak to anything interesting that comes up from the dog side of things with those different ecosystems?

Kyoko Johnson 36:32

Sure. So that photo that you just mentioned, from the photo contest that was from, like nine to 9500 elevation on Mauna Kea, and volcanic island or mountain on the Big Island. And yeah, so we were above the clouds. And I think that’s kind of what made for like an interesting image. Just walk in the clouds. Yeah. And I think that people don’t think so much. I mean, they’ve seen pictures of flowing lava, but they don’t think of the hard, hardened lava that you can walk on. And that’s a big part of the landscape here, especially the newer islands. So yeah, I mean, I’ve been up there before, but this was the first time I went up there with detection dogs, and it was very, very interesting and beautiful and amazing. The dogs had to wear, you know, protective booties, of course, because it’s pretty rough up there. Yeah, so Mauna Kea and Mauna Loa, all the mountains here are pretty spectacular. And that’s definitely not the image that most people have of Hawaii, Johnston Atoll, where I went last year, with the dogs to do the invasive and detection. That was an interesting place. I mean, it’s a little bit more what people might imagine whether it’s, you know, tropical, turquoise water, and, you know, some palm trees and stuff like that, but it was a former military base. They used to do chemical weapons testing, and, you know, storage and stuff like that. So there’s still a little bit of that left there. And it’s basically a flat island with an air plane runway. And now it’s kind of a little bit overgrown with just non native plants and stuff like that. But yeah, it’s not really the terrain that you’d imagine here. Just because it used to be a military base. So that was pretty interesting. And then of course Hanalei, we just talked about it’s, yeah, it’s it’s an amazing wetland environment. And again, not a place that people or the public is allowed to visit. So the they did make a new overlook where people can look at it, but it’s a little bit different from the typical image of Hawaii as well.

Kayla Fratt (KF) 38:47

I’m curious about working with dogs and those wetlands having not been there. Like, how, how wet is it? How bad are the dogs? Are they having to swim at points? Are they waiting? Or are you able to kind of navigate on some some bits of solid land?

Kyoko Johnson 39:05

Yeah, that’s a great question. So most of it is on the grass and mud. So we’re circumnavigating the taro fields. And the reason that it’s focused more on the taro is that the botulism tends to not happen in the wetland units as much as the taro and they think that it’s you know, has to do with water quality level, maybe fertilizer, it’s being investigated and worked on as well. But so yeah, most of it is walking on mud and dirt. And then if the dogs detect something in the taro, then they would be sent into the Taro, but it’s wet Taro meaning it’s in water and mud. So, you know, last time I was there training, the dogs were maybe up to their shoulders, or between their fingers and their elbows in mud. So it’s an not necessarily an easy area, easy place to walk.

Kayla Fratt (KF) 40:03

That sounds exhausting for the dog and the people.

Kyoko Johnson 40:05

I mean, they only need a short distance from the dike to the carcass. But you kind of need a combination of dog that has the drive to walk through that kind of mud. But it’s also not a total dive bomber who’s gonna destroy the plants and stuff like that. So it’s a fine balance for sure.

Kayla Fratt (KF) 40:25

Do you have for for those of us who may not know what Taro is? I have no idea. No, no, that’s okay. Um, so you can explain it? And then as well, do you have any photos that you’re allowed to share that maybe we could drop into the show notes?

Kyoko Johnson 40:40

Sure. Yeah, I’ll send you that later. But Taro is a route plant, kind of like a potato, except it has like a long stalk that grows above the water, and big leaves above it. So the Hawaiians use the leaves for all kinds of cooking as well like luau food and stuff like that, as well as the root. There are some people who grow this plant dry, but the water protects it from predators. So that’s helpful for the farmers here.

Kayla Fratt (KF) 41:14

Cool. I’ve never had it, I have no conceptualization of what what this is, so I’m gonna have to do some Googling later. Happily.

Charles Van Rees 41:28

So my next question for you Kyoko is one that I thought of immediately when I very excitedly got involved in this interview, which was when I think of Hawaii and my time there it is a place that is yes, very, very weird in very good ways. That leads to such special and different experiences in the outdoors. As a naturalist, I find that it’s such an overwhelmingly different and fascinating place. When you’re doing conservation work, especially in Hawaii, there are lots of areas that are the people overlook when they’re visiting the islands. I think that people go to the beaches, they go to Honolulu, what have you, and they’re gone. But there’s so much more to those islands. And there are so many special amazing places and special amazing organisms to see. What kind of things have you you know, in your position, and especially working professionally in conservation? What have been some of your favorite and most special places, and plants and animals that you have come across in your work?

Kyoko Johnson 42:36

Wow, there’s so much that it’s hard to just say one thing. I guess the great thing about doing conservation dog work is it’s not limited to a specific species, you get to work on different things, which I love. So, one thing that comes to mind that I haven’t mentioned is are the endangered snails that are up in the mountains here. Yeah. And we actually tried to do a project detecting the invasive cannibal snails that attack these native snails but we just found dogs are not the best use for this unfortunately, because these in predator snails were very, very hard to detect, especially under leaf litter and in the environments that these snails live. But yeah, so as part of exploring this project, we got to go up to the mountains and visit the exclosures that these snail extension extinction prevention program and other snail people have built to keep the predators out which includes the invasive snails, rodents and Jackson’s Chameleons, reptiles. So, yeah, I got to see the tiny little beautiful snails they have stripes a lot of them have these stripes on their shells. And that was pretty special. Just because it’s something so unusual and you know very different from what you think of Hawaii like turtles and dolphins you know? And stuff like that. Yeah.

Kayla Fratt (KF) 44:05

Yeah, I think did you share some photos of those guys and all their their cool stripes on your Instagram at some point?

Kyoko Johnson 44:12

I probably bring someone else yeah. Probably yeah.

Kayla Fratt (KF) 44:16

Cool. Yeah, yeah. I love that one of the things that comes to mind with the some of the coolest wildlife is the snail I think that just goes to show how how nerdy we all are you trying to say although hold up. I am not trying to throw shade at the sales. I would never. So I think we’ve already touched on this a little bit. But Charles was there anything more you wanted to say about why invasive species are so particularly harmful in Hawaii? You know, we know they’re problematic everywhere. Um, we’ve touched on that a little bit. But if you want to expand on that anymore.

Charles Van Rees 45:04

I guess one other thing to not to not paint too bleak a picture about the invasion ecology situation in Hawaii, there’s one, there’s one potential advantage to being on an island, which I think is represented really well by folks in New Zealand where there’s just a very strong I think conservation ethic and a lot of funding and public support for conservation measures, being on an island at least gives you the advantage that there’s a limited amount of this kind of battlefield against an invasive taxon of some kind, invasive species or population, what have you. So because there isn’t like an unlimited, you know, a virtually unlimited area for these invasive species to spread to like there would be on a continent, you can potentially kind of like square off areas and like, take territory back, you know, if you can protect certain areas really well. And eradicate those organisms, or manage them really effectively within an area you can have, you can have kind of safe zones. And in New Zealand, they’ve managed to clear, you know, entire small islands this way. So, I think, you know, some of this, the danger, that’s that’s posed ecologically by the small size of things can actually be to our advantage here in terms of managing them. So there’s sort of a glimmer of hope, you know, and there are a lot of new technologies with regards to excluding invasive species from bird nesting colonies and things like that, that are, yes, very expensive, but also being shown to be increasingly effective. So there are ways to deal with this. And I think we are getting a better handle on it. But generally, it’s just worth remembering that when you’re dealing with islands, most of the time, you’re dealing with invasive species, right? Relevant to those analogies, we were messing with earlier, immunocompromised individuals, or elevators or whatnot. Island systems are going to be more sensitive to invasion unless they’re molded up pretty much across the board. And so invasive species have their own kind of very unique conservation issue. But they happen to be one that also, you know, semantically relevant here, they also happen to be one that conservation detection dogs can make huge contributions to, because detecting invasive species is really important. I’m sure we’ll talk more about that in the future. But yeah, I think that’s I don’t want to end all of that on on such a super sour note. And I want to acknowledge that there are some strategic advantages to the situation that Hawaii is in. And there are success stories that we can learn from and hopefully expand upon.

Kayla Fratt (KF) 47:52

Yeah, and Kyoko you’ve worked with. So we’ve mentioned the devil weed, which I’m assuming based on the name, it’s not soft and nice smelling, but I could be wrong. And then we also we’ve mentioned the coconut rhinoceros beetle as well. So you’ve worked on a couple of different invasive projects, what are some of the particular considerations you as a dog handler and trainer are thinking about with working with invasive species? And what do you find rewarding about that work?

Kyoko Johnson 48:19

So the coconut rhinoceros beetle is not a project that we are working on, I just promoted a position that they had open and fortunately, one of our devil weed handlers actually got the job. So now she’s doing the devil weed, as well as the coconut rhinoceros beetle. That’s really cool. Yeah. But, so your question was, what are the considerations and dealing with invasive species? Yeah, yeah. So I think that it depends on the species depends on the island and stuff. Like, for example, Devil wheat is pretty established on Oahu. And there’s not a big chance of complete eradication here. So it’s more in the containment phase. And so, of course, we still are very careful to decontaminate our gear and not go out there during like the full on seeding season. Because we could exacerbate the spread. But yeah, as far as training samples, for example, it’s not regulated on Oahu, so we’re able to, you know, pick them and bring them home for training. And just when it’s flowering season, we’ll cut off the flowers or something but on the Big Island, where it was recently discovered, it’s still very new and they want still have a chance of eradicating it. So, you know, I don’t think that you know, just the random person is able to, you know, pull the weed and take it home for training or something like that. Yeah, so yeah, it does depend on on where you are.

Kayla Fratt (KF) 49:51

Yeah, that makes sense. When I was in Montana and this was back at working dogs for conservation, but the permitting process to get zebra mussels was crazy. But then when if I went home to Wisconsin where I grew up, I could walk off the edge of my grandparents dock on a lake and just pull a hunk of zebra mussels out of the water and use them to work with Barley. So I actually did some some stuff where I just if I was going home, I would just train Barley with Zebra mussels that I could pull out of really established areas in Wisconsin, and then just not bring them home to Montana, where they’re not established yet. And I know similarly, one of the things we were thinking about back at working dogs for conservation working with Dyer’s woad, which was one of the plants we worked with was we were walking, this is the only project I’ve ever done as a conservation dog handler where we were walking, five meter transects and just really trying to find every single plant. So is that something that you do as well? Or?

Kyoko Johnson 50:48

Yeah, no. So with Wahoo devil weed, we do not do that. Because like I said, it’s so established that there’s really no chance of finding every single one. I mean, if it were at the point where, you know, there’s only a few left in in on the island, then we would do more pattern searches and stuff like that. But right now on our island, that’s not really practical. We did get contacted by the Big Island invasive species committee, though, to possibly do some work with the dogs on their island. And, you know, over there, we might do something more like that, like with, you know, a more specific search strategy to make sure that we don’t miss anything. Yeah.

Kayla Fratt (KF) 51:35

Yeah, that makes sense. So I know, Carl’s has to go soon. So we had two little questions left one that I think we’ve already answered, but Kyoko is going to give you a chance to bring up anything else that we haven’t brought up yet. As far as specifically with the Hanalei National Wildlife Refuge, what are some of like, why are the dogs so important for the research there? If you haven’t mentioned, if there’s anything you wanted to bring up that you haven’t yet there?

Kyoko Johnson 51:58

Sure. So it’s no longer a research project, it’s kind of an operational program. But the research project was important a few years back in order to, you know, kind of establish the efficacy of the dogs in that particular environment for that application. I think because as you know, in the conservation world, there’s so many different applications, every location is unique, and the needs are unique. So you can’t just say, Oh, the dogs do great at the wind farm finding, you know, bird carcasses, so that means we can, they’re going to be good everywhere for all applications, you know, so it was important for us to do the research study, to show that and to compare, you know, human visual surveyors versus dog teams versus ATV and stuff like that, and what’s good about each method. And so what the study found was that, you know, the visual surveys complemented the canine assisted surveys, so they didn’t necessarily find the same targets. And I think that’s a really cool thing. To be able to say that these two methods together can help find more instead of Oh, the dogs or, you know, the magic bullet or something like that. Yeah, or dogs don’t work at all. Yeah. So yeah, as far as you know, just the program now, you know, it’s it’s only been several months since the program started. But, you know, again, we’re finding the same type of thing, as we did in this study where the dogs are finding, you know, different targets than the humans are. And so far, the botulism level has been low. And, you know, we don’t know, we don’t have enough data at this point but we’d like to, we hope that you know, the dogs are contributing to keeping the botulism low.

Kayla Fratt (KF) 53:43

Yeah, that’s great. Well, Charles, I know you need to go. So thank you so much for being here. We’ll talk again soon and everyone who’s listening, hang on, we’ve got one more really cool question with Kyoko about her sniffer rat program, so don’t leave yet.

Kyoko Johnson 53:58

It’s so nice to meet you. Charles

Charles Van Rees 54:00

Kyoko, so nice to meet you. Thanks so much for coming and chatting with us. And of course, Kayla, thanks, once again for for having me on the show. And a big thank you to our listeners. It’s really exciting and nice to to engage with it with a new audience here and yeah, really, really grateful to be a part of this. So thanks, everybody, and see you next time.

Kayla Fratt (KF) 54:20

Thanks, Charles. So Kyoko as I said, right before we let Charles go. You have a really cool program that you’re just starting on with some sniffer rats. Why rats? What’s the project and where are you at with it? Where are the what are the goals? You know, I know that’s like 17 questions, but just yeah. Tell me about the rat program.

Kyoko Johnson 54:41

Sure. So what made me think of this idea was you know when I worked at Hanalei, you know the dogs ideally we’ll go into the taro and find the targets but there are some, you know, units taro units where they’re just way too big for the dog to effectively you know, If anything sticks through the entire unit, so made me think, Oh, I wonder, you know, if we could send a rat in there on a boat, and then they could press a button and let you know, when they smell a target, like running them crosswind in transacts, or something like that, that would be so cool. And not just for that particular use, but you know, I thought of putting rats on drones, and, you know, monster trucks and I don’t know, just different vehicles to access terrain that is difficult for the dogs are dangerous, perhaps. And I know that some people put dogs on kayaks and boats and stuff like that. But you know, there are certain locations where you can’t do that. Pretty big. Yeah. And, you know, of course, everybody knows about the landmine detecting rats. So it’s kind of well known that dogs have good olfactory system, and they are able to do it if they’re trained, right, and the right ones are picked. So that was my idea. But at the same time, you know, we were trying to look into the rodent mongoose like an invasive mammal detection program. So I decided to get some rats of my own because it was hard to find, you know, pet rat owners who are willing to let us use their pets as training aids for the dogs. You know, it’s this idea of dogs hunting invasive rodents is a little bit scary. You know, if you have your own pet, right, so I got my own. And like, I had no idea that I would totally fall in love with them and become, you know, crazy rat lady. Yeah, they are. They’re so intelligent, and anything I’ve trained them on so far. I mean, they pick it up immediately, like a new target odor or targeting or, you know, whatever it is. So, I think yeah, the training part is going to be actually the easier part of this project. And it’s been more learning about, you know, rat behavior. What are the best reinforcers to use? Like, how do you pick the best working rat? Who wants to do this kind of work?

Kayla Fratt (KF) 57:06

I was gonna say, yeah, do you have high drive rats? Yeah.

Kyoko Johnson 57:11

Definitely, I’ve actually found the lower drive, or I would say less food motivated ones, tend to, at least in my experience, have been a little more affectionate. They want to cuddle. And they also found that they don’t like vegetables for some reason. The ones that don’t like vegetables are also not that food motivated. It seems. So yeah, I learned some curious things. And of course, you know, that may not be true for all rats, but that’s what I’ve experienced. So it’s been interesting testing, food reinforcers. And also just learning about their behaviors in general, like, what are some of the alert behaviors that might be conducive to rats? Like, you know, the same with chickens, for example, if you’re training them, they are likely to, they’d like to pack things. So it’s an easy thing to train them to do on cue. So that type of thing. Yeah, and then what’s probably going to be more challenging is also the actual application because I did speak with the people at the refuge. And, you know, they liked the idea, but they’re like, Oh, well, you know, it’s gonna take about three years to get a permit to put a remote control boat in the refuge. It’s like, oh, I hadn’t even thought of that. Okay,

Kayla Fratt (KF) 58:26

yeah, it’s gonna be generation, like two or three of rats at that point.

Kyoko Johnson 58:31

Yeah, exactly. So I think at this point, I’m not. My goal is not to do this at Hanalei, but to just test the method in Yeah, just controlled environments to see what works best with equipment like the boat and the doorbell or whatever they push to alert and the camera that you put on the boat and stuff like that.

Kayla Fratt (KF) 58:54

Wow, that just sounds like such a cool project. I know one of the I’ve always had this dream. So I got my start as a bird trainer. Before I ever trained dogs, I trained birds. And I’ve always had this this wacky dream in my head of trying to figure out how to convince some vultures to work for me. Oh, yeah, I think it would only really work well for things like Cadet like to, to augment like a missing person search or like a cadaver dog sort of search. Because I imagine it needs to be such a big odor cone for high flying bird to find it. But I know there was some some guy in Germany and like the 50s or 60s or 70s. I can’t remember who tried it and didn’t have much success, but he might not have. I would hope that maybe with a bit of bit more knowledge of ethology and ABA, you might be able to get a little bit further.

Kyoko Johnson 59:43

Yeah, and I don’t know if you’ve heard some of those podcasts about falconry. But there are people who use raptors in conjunction with their hunting dogs. Yeah, the birds will detect something visually and then the dog will help flush it or something like that.

Kayla Fratt (KF) 1:00:06

It’s one of those things that. Yeah, I don’t know anywhere near enough about to start on as a project. But I’m hoping one day, I’ll have the opportunity to have my own experiments with some multispecies work. Be great.

Kyoko Johnson 1:00:19

And I’d be happy to volunteer and help you.

Kayla Fratt (KF) 1:00:22

Oh my gosh. Yeah, we should have Yeah, the word the conservation detection animal network. What are your rats names? And how many do you have?

Kyoko Johnson 1:00:33

Right now I have three. The oldest one is Tony. I named him two tone Tony, because he has the gray cap, and then the white body, Tony, and the younger one that is also two toned is Jr. because he looks like a younger version of Tony. And third one is Nahenahe, it’s a Hawaiian word. That means gentle. He was the most gentle baby rat. And of course, he actually turned out to be the most food motivated, I think, trainable rat.

Kayla Fratt (KF) 1:01:03

Oh, interesting. Yeah, that’s funny. Yeah, I look forward to your your papers on rat temperament testing and helping screen for rats. Maybe by the time I’m ready to start exploring multi species detection work, I’ll be able to learn a bunch from you. Is there anything more that you wanted to talk about? I just realized we asked about your rats. We haven’t asked about your dogs so we can talk about them. And if there’s anything else you wanted to bring up before we wrap up?

Kyoko Johnson 1:01:30

Um, no, I yeah, I think that was that was great. Really appreciate you having me on the podcast.

Kayla Fratt (KF) 1:01:38

Yeah, no, I really enjoyed this. And I’m looking forward to doing a part two and three and who knows what else going forward?

Kyoko Johnson 1:01:46

I look forward to that.

Kayla Fratt (KF) 1:01:49

Yeah. All right. Well, Kyoko,mwhere can people find you online? If if they haven’t figured out how to find you yet. And we’ll of course include all of that in the show notes as well as I made a note to find that that study that you mentioned from Hanalei, and all the photos of the Tehran, all of that?

Kyoko Johnson 1:02:05

Sure Our website is www.conservationdogshawaii.org. Our Instagram and Facebook are both conservation dogs, Hawaii. We do have a Twitter but we always forget to post on there. So I think Instagram and Facebook are the best for now.

Kayla Fratt (KF) 1:02:23

Okay, great. Well, yeah. And again, we’ll have all of that in the show notes along with everything else that you always find in the show notes for the show. Thank you again, Kyoko and we’ll talk again soon.

Kyoko Johnson 1:02:34

Thanks, Kayla. Bye.

Kayla Fratt (KF) 1:02:35

Bye. Thank you so much for listening. I hope you learned a lot and are feeling inspired to get outside and be a canine conservationist in whatever way suits your passions and your skill set. This week’s call to action is to review canine conservationists yet again, on Apple podcasts. It’s been a long time since we’ve gotten a new interview it looks like as of recording in December, our most recent review was in September. So if you haven’t yet, please do take a moment to go on over and review us over on Apple podcast. It really helps other people find the podcast and it makes my day. You can find show notes donate canine conservationists hire us or join our Patreon over at canineconservationists.org. Until next time!

Donate

Donate