For our fifth episode of our odor discrimination series, Kayla talks about the odor discrimination work K9 Conservationists did with Action for Cheetahs in Kenya.

Science Highlight: None this week

Links Mentioned in the Episode:

None

Figures Mentioned in the Episode:

You can support the K9 Conservationists Podcast by joining our Patreon at patreon.com/k9conservationists.

K9 Conservationists Website | Merch | Support Our Work | Facebook | Instagram | TikTok

Summary

By Maddie Lamb with the help of Chat-GPT

In Spring 2022, experts Kayla, Rachel, and Heather collaborated at the Action For Cheetahs in Kenya (ACK) to refine the training regimen of scat detection dogs, particularly two named Madi and Persi.

The Central Issue:

- Madi had a 98% success rate in identifying scats, while Persi, younger, had her prime training years during COVID.

- Both dogs frequently mistook leopard and caracal scats for cheetah scats.

- Initial training involved telling the dogs “no, search on” when they falsely alerted. However, this method wasn’t reducing the false alerts.

Identifying Root Causes:

- Dietary Factors: Rehabilitated cheetahs might have had different diets, affecting the scat profiles.

- Storage Contamination: Scats stored in permeable plastic containers in shared spaces risked scent contamination.

- Training Overemphasis: There was potentially too much focus on the act of alerting, rather than the correct identification of scents.

Strategies and Solutions:

- Kayla initiated a significant shift by stopping the presentation of non-target samples.

- The “matching law” theory was invoked, underscoring that you get the behavior you reinforce.

- New storage methodologies were developed to counter contamination, focusing on minimizing cross-scent issues.

Lessons from Barley:

- Barley, during an expedition in Guatemala, developed a penchant for alerting to a fruit named chicozapote.

- With strategic interventions and the “no, search” cue, Barley’s false alerting was quickly corrected.

Tailored Training for Madi and Persi:

- Both dogs underwent specialized training regimens.

- A data-centric approach was adopted using Google Sheets to track metrics like false alerts, correct dismissals, and misses.

- Training areas were strategically expanded, setups were adjusted, and the team navigated challenges like extinction bursts — periods where the dogs increased false alerts before diminishing them.

- Intense focus on Madi revealed his false alerts decreased in duration but persisted in frequency.

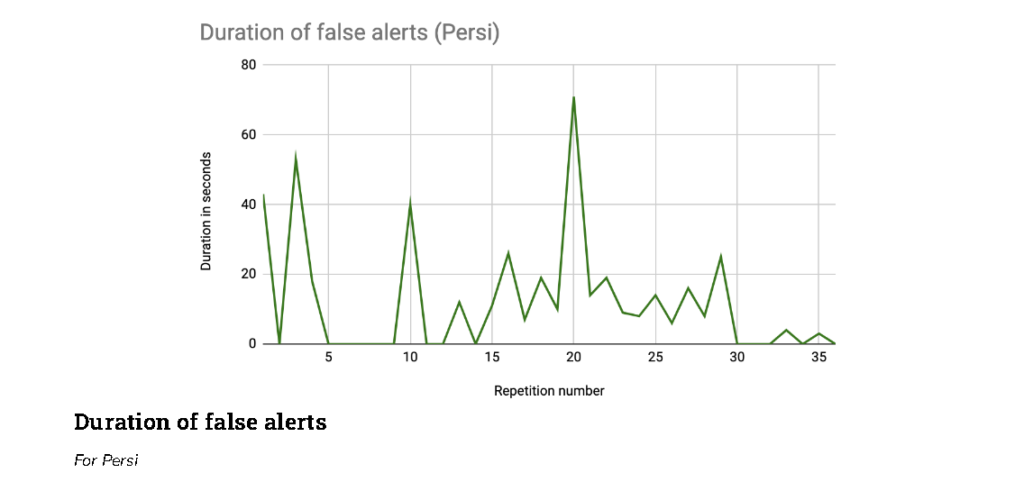

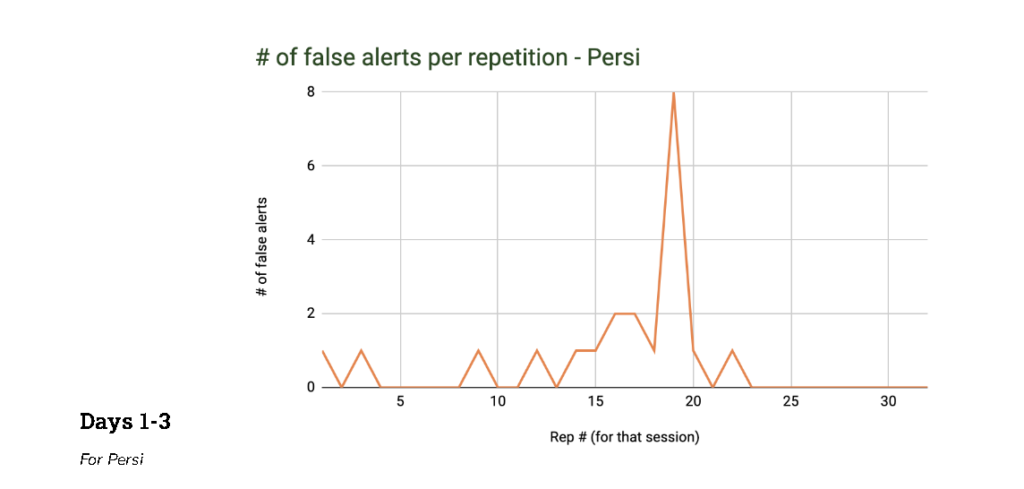

- Persi, on the other hand, faced her largest spike in false alerts during her extinction burst but showed significant improvement thereafter.

Evolution of Training Protocols:

- Training methodologies incorporated movement exercises for handlers, advanced search strategies, and field safety protocols.

- Progression criteria were established, ensuring dogs consistently met set benchmarks before moving to more advanced training levels.

Concluding Insights:

- After an intensive six-week program, Madi’s and Persi’s abilities to discern scents saw marked improvement.

- The team remains vigilant for potential behavioral regressions, underscoring the need for adaptability and ongoing refinement in training approaches.

Transcript (AI-Generated)

Kayla Fratt 00:09

Hello and welcome to the K9conservationists podcast, where we’re positively obsessed with conservation detection dogs. Join us each week to discuss conservation biology, canine welfare, population genetics, eDNA and everything in between. I’m your host, Kayla Fratt, one of the cofounders of K9Conservationists, where we train dogs to detect data for land managers, researchers, agencies and NGOs.

Today I’m here for a solo episode to round out our discrimination miniseries, we’ve got a couple more episodes coming up. But today I’m here to talk to you about the work that we did, specifically while we were in Kenya with the scat dogs from action for cheetahs in Kenya, in order to reduce false alerts and kind of improve specificity. With those dogs. This is built off of a talk that I gave at the conference at the International Association of Animal Behavior consultants, and it should be quite interesting. It’s a little bit data heavy, we used a protocol called Differential Reinforcement of Incompatible behavior, as well as a procedure known as extinction in order to eliminate the false alerts with these docks.

So as a recap for anyone who maybe doesn’t remember or is new to the podcast, in spring of 2022, myself, Rachel, and Heather took turns flying to Kenya to help work with the scat dogs at action for cheetahs in Kenya. What they were dealing with was that they had two highly trained and experienced conservation detection dogs, but had recently lost through kind of COVID and related factors, they had lost their entire dog team staff. So they had two new staff members who both had never trained dogs before.

So our job was to come in and help work with the handlers on the dogs to make them a team that was ready to go though some relevant characters here are going to be Madi. He is a seven year old Border Collie Rottweiler mix, Persi, who’s about a three year old Malinois, Edwin, who is the handler, one of the handlers with Action For Cheetahs in Kenya, who’s got background in an agricultural sciences. And Naomi, who was the other handler at Action For Cheetahs in Kenya and had a background in conservation. You can hear both of their voices as well as the voice of Action For Cheetahs in Kenya Executive Director Mary White extra in previous episodes of this podcast.

So in past work with Madi where he had done fieldwork, he had been up to 98% correct with with the scats that he identified. Persi had never been fully fielded, because as we said, we did this work in spring 2022. And Persi was just shy of three at that time. So she had spent kind of the bulk of her prime working years and prime late training years during COVID. So in recent training, both Madi and Persi were frequently alluding to leopard and Caracal scats that were placed out in the training room.

There was another consultant heading to Kenya shortly before me, and then following me, Heather and I were to overlap, and Rachel and Heather were going to overlap. So we were going to have about three months of continuous work from the from the canine conservationists team. But because there was another consultant heading to Kenya before me, I kind of took a step back on training plans during before coming to Kenya. And when I arrived in Kenya, the approach and training the dogs was to tell the dogs to “no, search on” if they made a false alert. And in training, they were training in a small scent room where there was always a correct answer. So generally within seconds after the false alert, the dog would encounter a cheetah scat and then could make a correct alert and get rewarded.

So while this worked in the moment, it did not seem to be decreasing the false alert behavior over time. That’s where I started digging into records. At this point I was on the ground in Kenya and action for Cheetos in Kenya had a strict record keeping rule regarding the care and training of their dogs. However, their system for maintaining the records long term and what to put into the records was a little bit less clear. So there was one notebook of handwritten notes that was nowhere to be found. And then the training log that we did have on hand would say things kind of along the lines of session with Persi at 1pm 32 degrees Celsius, northwest wind at nine miles an hour or 20% humidity, good energy and focus.

So there wasn’t very much information as far as which samples were being used in training. And we couldn’t really look back to see what had happened as far as a specific sample or a specific point in time where this problem had occurred. And again, since Edwin had only been hired about four months earlier and named Naomi about three months earlier, she they weren’t going to be able to answer any of those questions.

So I did go through and interview some of the other staff members at auction for cheetahs in Kenya. But memories were a little bit fuzzy. It sounded like at some point there may have been a mislabeled Scott that was marked as cheetah but was actually can’t recall or vice versa. Or perhaps there was a single sample that had consistently given the dogs issues earlier on in training and then the problem had ballooned, or perhaps both.

Long story short though the issue had never really gone over A and have now expanded to just overall really low specificity in the training context. The dogs hadn’t been in the field for a while. So we weren’t really sure how the problem was going to present in real searches. So for my first two weeks or so on site, we basically continued with the plan, we put samples out, where we would say, “no, search on” if the dogs made a false alert, and, again, we just weren’t seeing this problem go away; the false alerts were not reducing. So we had to change something.

What we did at this point was, we put a full stop to presenting the dogs with non target samples. And I started to think and reach out to a bunch of other mentors. So of course, I started with Google and a couple searches on false alerts really didn’t help much. Most of the articles online focused on helping dogs not to alert to trace fringe or resident residual odor, which wasn’t really the issue here. Several other articles focused on competitive node work nosework and handler related issues calling regarding calling alerts to early pushing the dog into making an alert with body language or miss reading a dog who’s got an unclear alert behavior, such as nosework dogs that do a pause or look back. So other keywords retrieved articles highlighting just how pervasive this problem is from police canine so like expository articles about false alerts, but really nothing came up that was giving me an insight on how to how to remedy this problem from a training lens.

So when I first brought this problem up to some of the senior staff at the ACK, they suggested that handler cueing was the problem, which again is similar to what those nosework articles had said. And that was a hypothesis that we could more or less test right away. So I asked the handlers to plant their feet, put their hands behind their backs, and stay in the same spot from where they released the dog, and let the dog search the scent room off leash. And this did nothing to affect false alerts.

So next off, I kind of went into the conservation dog literature and discourse and you know, memories from working with my own mentors, all of the podcasts that we’ve done here, as well as podcasts that I listened to on James Davis’s show and elsewhere that I’ve heard folks talk about conservation dog work. And there have been conservation dog, folks who have mentioned that consistently training dogs with a negative or an off target sample can be problematic. And the way that I’ve basically understood this to be is that if you do a lot of repetitions in a scent room, or a training scenario, where the dog becomes familiar with the scats and is being exposed to those samples, while they’re in kind of the emotionally heightened state of an excitement of training, then when they’re later out on out in the field that may cause like a flicker flicker of recognition when the dog is tired, a bit of dopamine because that scent is linked to the pleasure of training in the brain. And then we get a false alert. So that’s a pretty common hypothesis. I know I’ve heard Rogue Detection Teams and Working Dogs for Conservation both kind of have similar ideas. I think part of it is also if you’re not being perfect about your odor hygiene. And then when you’re out training the dogs with you know, an off target, Scott, you could also be crossed, cross contaminating things or getting kind of your odor. And even no matter how perfect you are Scott that comes kind of out of the fridge and then is placed in the environment might have things in common with your training samples that again, could kind of be really reducing the dog’s ability to stay specific.

So that this whole thing kind of makes sense to me in a way. But it didn’t quite fit in with what we were seeing with the Action For Cheetahs in Kenya team. So anyway, the dogs weren’t just making mistakes in the field after long days, but they were making the mistake in training. The dogs weren’t just tired or confused by a flicker of recognition on a long search. They truly didn’t understand the difference in a single simple task in a sunroom. So next up, I spoke to Paul Bunker and Dr. Simon Gadbois, who are both parts of this discrimination miniseries about the issue. So both of them had the same question for me, is there enough difference between the samples for the dogs to tell the difference without kind of more specialized training.

So we had a couple of different points that we explored together here. So one, the samples were acquired from orphanages and rehab centers, which means that the animals weren’t eating natural diets and could be medicated or supplemented. For some dogs this can make it challenging to swap from training targets to wild symbols because they don’t recognize them as the same thing. So you can imagine if you’re used to sniffing giraffe poo, that is from a female giraffe on some sort of birth control who is also receiving an antibiotic for health infection, and that is all the dogs are trained on and then they encounter a wild sample from a female lactating or pregnant female that is not obviously on antibiotics because she’s wild, the dog might just not recognize it.

However, for other dogs like Persi and Madi, the different problem here is that in the wild cheetah, caracal, leopard aren’t generally eating the exact same diet. Cheetahs like gazelles, you know, little Thompson gazelles, leopards really love Impala and Kara Cole go for much smaller things like dictates and hairs and birds. So paired with medications and supplements, the training scats smelled more similar to each other than other wild scats truly would. So we were asking the dogs in training to do something that was likely harder than what it would be in the field. And we just didn’t have enough field samples to use at the time to see if the dogs reacted better with field samples, or to just switch over to training exclusively with those wild samples.

So next up, we had the how the samples were actually dried and stored. So the samples were all dried in the same open air room, leading to potential contamination, as air moved from one sent, the air is moved sent from one Scat to another. Worse, these samples were then stored longterm in plastic that was not species specific. And that’s important, because plastic is permeable, things that go into plastic come out smelling a little bit like plastic, and the plastic comes away smelling a little bit like what whatever was in there, all of the samples, therefore smelled a bit like plastic and probably all smelled a bit like each other. They may even smell a little bit like old samples that had occupied the container that they were in now. Because it’s not like they had containers that were always used for cheetah or that they got rid of containers after a sample was retired, they were washing and reusing them. And that’s not a huge deal if you’re working with like glass, or metal, but can be really problematic with plastic.

For a quick test of this particular hypothesis, I pulled out a few of the plastic containers that had been used previously, but had been washed and were kind of in storage, ready to go for a new sample and both dogs alerted to them, but with a little bit less speed and confidence in their typical alert. So then finally, my kind of pet hypothesis was that I was suspicious about the actual setup of the training and kind of the how the matching law may be coming into this. And the matching law is basically the idea that you get what you reinforce. So if you spend a lot of time practicing behavior, a not a lot of time practicing behavior be when you pull out your treat pouch, and your animal is kind of throwing behaviors at you trying to figure out how to get reinforcement, you’re much more likely to see a higher proportion of behavior a than behavior B. And this can apply in a lot of situations other than just kind of potentially poorly set up shaping sessions. But that’s just like an example of where we might see the most often. So the handlers it at ACK had spent a lot of time learning from explosive handlers, which is the biggest detection dog industry in Kenya due to terrorism. And for good reason, explosive handlers tend to be very focused on the dogs alert, the dog can’t touch the sample, and must maintain a perfect sit stare alert until the handler can take appropriate action. The ACK team spent a lot of time focusing on the alert. They were doing repetition after repetition to get snappy, focused clean sets. And if the dogs worked hard or long in a sourcing puzzle or a nerd search, and then didn’t perform the perfect alert, the alert was fixed before we’re waiting the dog. So basically, the dog learned that the alert was by far the most important part and even on kind of a job well done with the seeking and sourcing. The alert had to be perfect in order to get rewarded.

So the ACK team was basically spending so much time training the alert that I was worried that the dogs thought their job was to alert not to actually discriminate odors or find the correct order. Another reason that I liked this hypothesis or another reason I kind of suspected this was part of the problem was that dogs can be astonishingly efficient in training. As soon as they encounter an odor that met some criteria. You know, it wasn’t that they were alluding to everything we put out if we put out Cat A domestic cat, or goat Scat, we weren’t getting this problem. But as soon as they kind of had an odor that met some criteria in their heads, the dog sat and as soon as they sat they got information in the form of either award or being told no search on.

So there is basically behavior train happening of odor to sit to information, which leads to opportunity of reward or the reward again, it may have actually been faster to discriminate between leopard and cheetah and caracal or caracal and cheetah for the dogs. But that requires a lot of concentration. And it might just be easier to alert to everything as a way to ask for help. And in a way all of the alerts were being reinforced, because the true alerts were being reinforced with toy play and the false alerts were being rewarded with information that led the dog to the next alert and therefore their reward.

And I think it’s really important here to kind of pause and say that their approach of telling the dog “no, search on” is not something that universally leads to this problem. So I’m gonna, we’re gonna tell a little story here that I think I’ve told before on the podcast, but it’s really illustrative and it needs to come back in here.

So here goes while I was in Guatemala with Barley about a week into our project searching for felid scats. One of our field techs offered me a delicious apricot like fruit called a chicozapote that the tech had picked from a tree on the trail. I ate a little bit of it and and then shared a little bit with Barley and we carried on our search and found a couple more scats. Pretty small nonevent.

And then the next day we went to a different area and there was far fewer scats it was a much less dense area, but Barley kept on alerting to chicozapote, and interestingly, he was specifically alluding to fresh fall in chicozapote that had either broken on impact or had been eaten a little bit by some sort of herbivore. So at each chicozapote, I told him “no, search,” which is almost the exact same cue that Edwin and Naomi were using for Persi and Madi. I also started asking a partner to check what Barley was alerting to so that I didn’t have to approach Barley and kind of risk that anticipatory dopamine dump that happens as dogs kind of expect to get their reward. Because seeing me approach him with the toy pouch on my hip is definitely enough to reward barley even if I never give him the toy, or, you know, reward him on a neurochemical level.

And then within a day, Barley stopped alerting to the chicozapote, and has never done it again sense. And it was, you know, it was a very stressful day. For me, this was the first time that something like this had happened. And Barley probably made somewhere between eight and 15 false alerts in that day. And he did, he made some finds, probably somewhere between two and four. But very, very stressful, the field team was a really good sport about it, because we had probably six or eight people in the field with us that day, which just adds a lot of additional pressure when something’s going on with your dog. But the point here is that there was, I use almost the exact same approach and was able to successfully eliminate this behavior in Barley. And so I’ve got a couple different things that I think are why that happened here. So we’ve got one being that the odors were really different between chicozapote and jaguar scat, ccelot, margay, puma, tayra, whatever it is, either way, they probably don’t smell really anything like this fruit. So discrimination was easy. It wasn’t that Barley was getting confused, or was getting overwhelmed with trying to make a difference, make the distinction between these things to this was a very new issue. So I was able to see that this approach was working and stick with it. And because we don’t really know the history of what was going on with ACK, there’s a chance that if they had used this approach right away early on, they may have had more success.

So then we had a long search and a hard search in between potential targets, which means that kind of getting informed that Barley was incorrect, wasn’t really a good opportunity for a reward. And it didn’t predict that he could go on and the next thing he found in the environment was going to predict his reward. So we weren’t getting that same kind of predictive power and behavior chain that ACK was getting.

I also did get harsh with Barley at times. And by harsh, I mean that I lowered my voice and or lowered the pitch of my voice and increased the volume. And that is more than enough to help Barley understand that I am displeased. I didn’t necessarily do that as an intentional training tactic, because I don’t try to intimidate dogs as part of training plans generally. But it happened because I was very frustrated. And that may have potentially helped as well.

And then we’ve also just got the fact that we’ve got different dogs and different learning histories. Barley is very highly responsive and could be described as a dog that wants to be right. He and I are very, very tightly bonded. And therefore kind of my body language and my frustration may have played off and influenced him. He also didn’t have that same history of an extraordinarily heavy reinforcement history for his alert, the same way that those that Madi and Persi did. And potentially that means that for Barley, it’s easier to understand that his job is to search and is to find the correct thing, because he doesn’t think that he never has thought that his job is to alert.

So I suspected that our job now was to teach Persi and Madi that the alert wasn’t what was paid, it was that the odor paid. This was going to have to be here paired with a strategy that effectively removed any and all reinforcement for the false alerts, particularly if we wanted to avoid climbing up the ladder of the humane hierarchy, which we’ll get into in a minute, and avoid kind of resorting to punishment for the dogs.

So first, I wanted to start out with some low hanging fruits, we threw out any unlabeled or old symbols, symbols that consistently gave the dogs issues and or symbols that we had and the symbols that we had a reason to believe may be contaminated. We then purchased a brand new storage containers for all of the scats and created a new protocol for drying and then storing the scats with three layers of protection between each species. So each new container was labeled species specific to ensure that over time, they would only contaminate cross contaminate between their own species.

And I will say that due to financial limitations for ACK, these containers were still plastic rather than preferred metal or glass storage systems. At this point, I do believe that another consultant Leo, who is continuing to work with ACK has at this point managed to get them over some other storage sample containers that are a little bit more appropriate than plastic.

Next up I started working through what our protocol was going to look like, I decided to opt for an extinction protocol, I had a hunch that the reinforcement for the false alerts was about information and expediency for the dogs. So I wanted to remove that reinforcement. We carefully removed the reinforcer for the unwanted false alerts will also have heavily rewarding the incompatible behavior of a curricular. So that’s why it was both kind of differential reinforcement of an incompatible behavior and extinction.

And now, I’d like to kind of take a quick pause and talk about least intrusive minimally aversive training on the humane hierarchy and talking about and how that played into this talk or played into this approach. So before jumping in to using extinction on Differential Reinforcement of Incompatible behavior, which from now on, we are going to call DRI, I wanted to ensure that we had adequately explored earlier steps within the humane hierarchy, which is an ethical framework that many Professional Dog Trainers adhere to as a way to help guide training decisions to while protecting the welfare of our canine learners.

So first up, there’s wellness. We had already been working on enrichment, clear training and appropriate exercise for the dogs. I’ve been working on handlers for their clicker skills, building puzzle toys, more cooperative bathing protocols, and cooperative care overall, for the dogs daily health checks. The dogs were getting long walks every day, they were getting training, they were getting agility sessions, the dogs may have been, the dogs could benefit from additional kind of human contact during their off time and kind of relaxing round their people. But overall, given the intensity of the work and the heat during their kind of the Kenyan days, the dogs seemed to be quite well, to me, they were under the care of a veterinarian, and I had no reason to suspect that this concern was a veterinary issue.

So next up, we get to antecedent arrangement. And this would be part of the training that we use by intentionally placing Scat samples in a way that made the correct choice easier and more salient than the incorrect choice for the dogs. The dogs were already being presented with the correct choice in each training session, which in some ways is contrary to best practices in detection dog training, as dogs should be introduced to blank searches where there is no target. quite consistently. However, we maintained the practice early on of making sure that there was always a cheetah Scat available. So the dogs always had something that was correct for them.

So then, then we have positive reinforcement. A key component to our of our plan was to heavily reinforced the dogs for their correct responses. And part of this was also reducing the criteria for a correct response. So earlier, I talked about the high criteria that the handlers held for the alert where they did the perfect focused, intense stare for several seconds at a time. And we shifted our informed reinforcement point to the moment that the dog sniffs cheetah scat. And then we progressed to just starting an alert with dogs like bending their hind legs and then moved on to reinforcing a full prolonged alert. I did expect frustration for the dogs as we started this planet, you can reasonably expect frustration every anytime you remove expected reinforcement for behavior. And this is especially true for the sort of dogs that we select from detection dog work, which are dogs that care intensely about their reinforcers and will work hard to get them no matter what’s in their way.

So we’ve essentially got a pair of dogs here that were selected specifically to push their own limits and keep trying even on lien schedules of reinforcement. So we were going to have extinction to work through and extinction bursts can be a bitch. So we essentially had a pair of dogs that were selected specifically to push their own limits and keep trying even on lean schedules of reinforcement, which brings us to the concept of an extinction burst, which is that we expected false alerts to increase in frequency, duration, or intensity before getting better.

I prepped the handlers for this phenomenon and emphasized that communication was the reinforcer that we were eliminating, not the toy because they were not presenting the toy for false alerts. But redirecting or correcting the dogs or helping the dogs out in any way was something we specifically could not do. And this was going to be hard on all of us because we’d like to be able to communicate with our dogs. But we really were hoping that through antecedent arrangement and smart training, we could reduce the intensity and frustration of that extinction burst.

I will say now knowing what I do now, which is I’m about a little bit more than a year out from when I worked as a consultant with ACK, I now would be taking a slightly more errorless approach where we would use occlusion seals on jars or like close tubers with holes drilled in the top for those negative off target samples and then have the target samples out in the full air so that the off target samples actually had less odor available to the dogs and use that as a way to help help ease them along and nudge them into the correct choice. That’s not something we did, but it’s something that I would do now and would have reduced frustration further.

So our overall plan was to set up small searches for the dogs for both cheetah and an off target Scat were available. The dogs would then be released into the area while the handlers stayed put as a way to reduce confusion from handler movement or verbal cues. At first, the cheetah Scat would be closer to the starting point in order to attempt to help the dog encounter that odor first. In each repetition in most cases, the scat locations would be rotated. At first, we would not put the off target scat in the location where the cheetah Scat had just been to kind of avoid tricking the dogs who both and Persi in particular had tendencies to check the most recent cheetah Scat placement first when released to search. So she would kind of go back to wherever that cheetahs cat had been. And at first, we were really careful not to put caracal or leopard scat in that location and kind of trick her. We did bring that in intentionally later on them. We then would click on reinforce the dog for sniffing, starting to alert or ultimately full alerts.

The cheetah scat, at first I ran the clicker, while Edwin and Naomi handled the Toy Play, which allowed me to control the timing and criteria for each repetition. And then if the dog was to alert to the off target scat the handler and I would not move or give any cues. And we just waited, we did have the plan to interrupt the dogs if the dog pawed at, mouthed, or otherwise interacted with the sample in a way that we didn’t like. And this luckily only happened once. Madi was given a verbal correction for it. And it never happened again, which is something that I think is really important to bring out. Because if you’ve got a dog whose frustration tendencies tend to be directed at the target, this approach would have to be taken, undertaken very carefully and potentially quite differently from how we did it. I want it to be really, really clear here that this is just the way that we did this one time. This is a case study.

Part of this thing that got us into this mess with ACK, which was that overemphasis on alerts was also what saved us, the dogs tended to false alert harder during their extinction bursts rather than aggressing towards the sample pulling out at mouthing on it. And that may not be the case for your dog at home if this is a problem you’ve got.

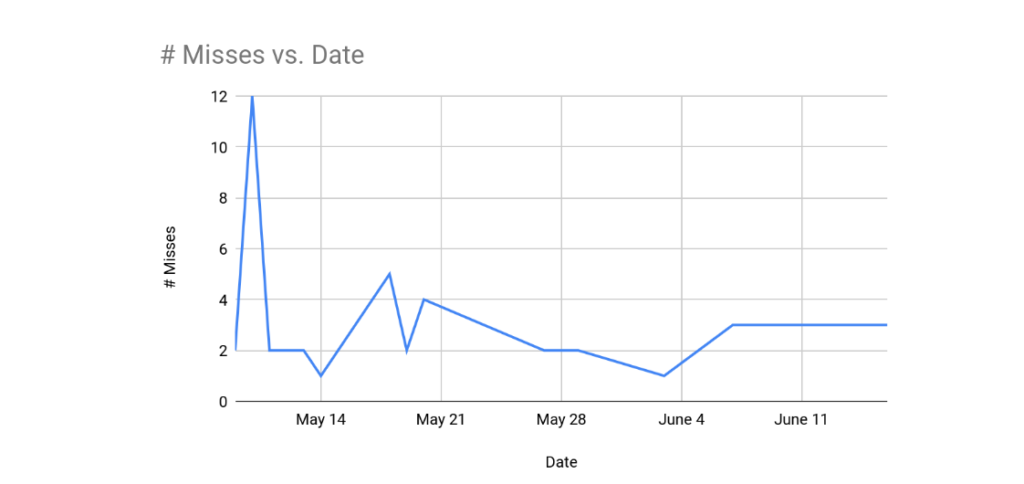

So next up, I started a Google sheet where we tracked the following items which were the date the dog, the handler, the ID of the cheetah scat, the ID of the nontarget scat, the repetition number that we were on within the session, and then our number of correct alerts our number of false alerts our number of correct dismissals, our number of misses, and the duration of each false alert as well.

So, just for some definitions here. A correct alert was when the dog sat at the cheetah scat, a false alert was if the dog sat at a non cheetah scat, for the purpose of duration versus number of false alerts if the dog took stepped, took steps away, and then returned to the scat that was counted as a second or separate false alert. But if the dog just kind of readjusted a sit, where they stood and stared or they stood up a little bit and then planted their bum again – all of that kind of within one alert event would count as one alert until the dog actually stepped away and then the clock would restart with a different alert, false alert, kind of number. And then we’ve got a correct dismissal and a miss which both in which we defined rather narrowly, just because we need this to be able to code things properly.

So with our correct dismissals, the dogs sniffed non cheetah scats and did not alert the dogs knows how to drop to indicate sniffing. We didn’t count passing by a scat without kind of a visible sniff as a correct dismissal, which kind of which may not be correct. And we weren’t doing this in a lineup scenario, we were doing this in more of an open area. So it was really hard to kind of say for sure if the dog had gotten older and we chose to be rather narrow with that definition. So the next amiss is if the dog sniffed a cheetah Scat without alerting, if the dog never checked the scat so they ran right past it or never approached it, we did not mark it as a miss. And again, we just kind of chose to define these things rather narrowly. Let’s see, what else. So then a repetition was kind of a from the word go to the completion of the reward sequence, and a session with a kennel to kennel period of time. So we would have a single session in a day that may include generally six repetitions and in a day, sometimes we did more than one session in a day and sometimes our there are more or fewer repetitions, but overall kind of a repetition is a smaller point within the session.

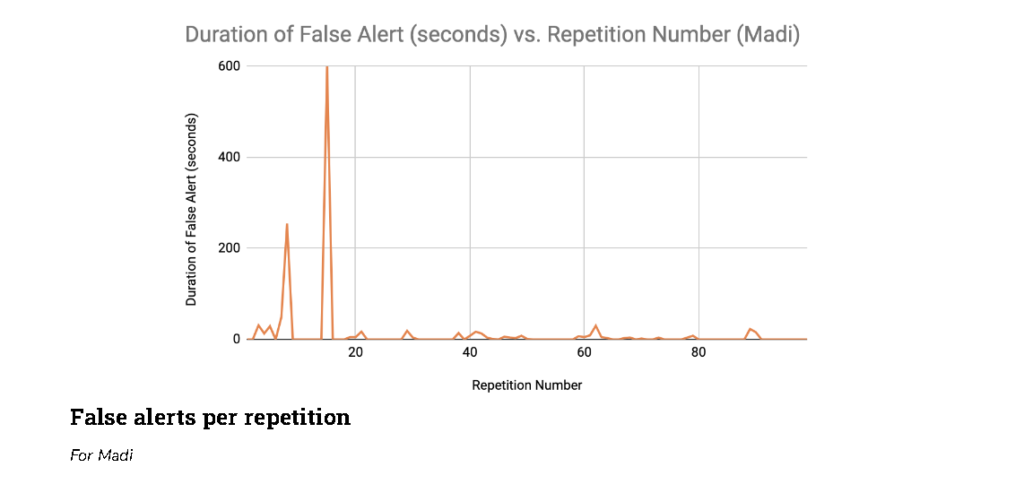

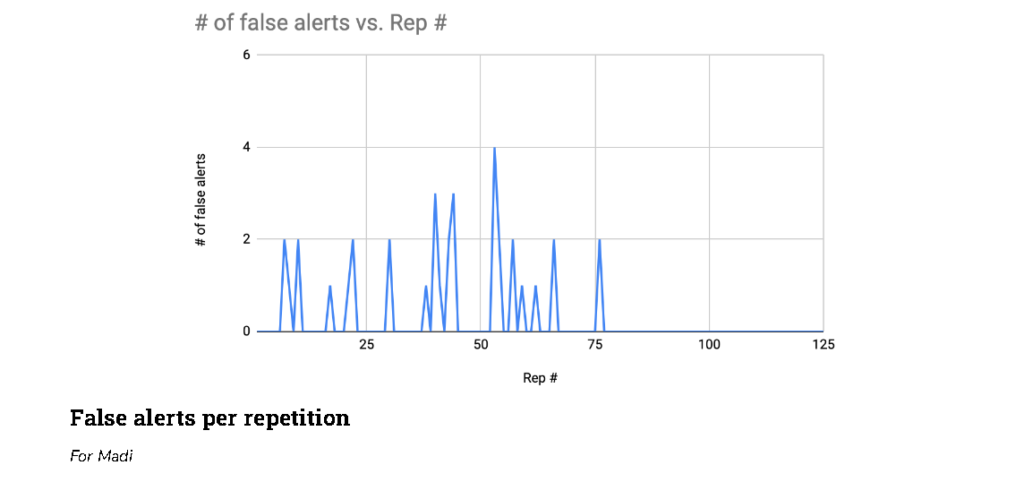

Then within our first three days of training, we saw very clear extinction bursts for both of their dogs and their false alerts. So for Persi, for her first 15 repetitions she was averaging zero to one false alerts per repetition. Those first 15 repetitions took place over the first day and a half. And then partway through her third session, which was in the afternoon of the second day. She had two false alerts in a row and two repetitions in a row, column. So she had two false alerts per repetition twice in a row, which was a change that was an increase for her. And then on repetition 19 a person had eight false alerts. And after that she only had nine more false alerts total four of which run the next three days of training.

I’ll include some of these graphs in the show notes for y’all so you can see these because these things are really kind of better visualized, in my opinion. So then we did look at Persi’s duration of false alerts and that just didn’t show quite as clear of an extinction burst. It does show her false alerts getting generally shorter over time. So within her 20th session, the average duration of her false alert was over a minute, which was the longest one so we had in repetition 19 She had a eight false alerts, and then in repetition 20 She had her longest ever false alert after that one in repetition 20. All of her false alerts were under about 25 seconds, with most of them lasting more like 10 seconds and then dropping off pretty sharply after a repetition 30 Her last couple falsehoods were all kind of under under 10 seconds very, very short.

So then we’ve got Madi, he’s a much more experienced dog with over 100 confirmed cheetahs scat finds under his collar. He’s a bit of a softer dog and isn’t quite as easily aroused as Persi. He likes to play with his toys, but isn’t kind of the sharpest, driviest dog around, which is different from Persi. She is a working bred Malinois from a kind of professional kennel. So Persi very much so was that like typical, very, very, very toy oriented, very intense working dog. And this is really interesting to me to point out because overall Madi’s false alerts were harder for us to get rid of over that first that month or so of training that we did. Madi had far more resurgences than Persi. And at first it surprised me because I would have expected the less driven dog to make fewer errors of commission. So I kind of the way I’ve always thought of it is that if a dog is absolutely desperate for their reinforcer, I would kind of expect that dog to gamble more. But Madi’s behavior suggested that perhaps because the ball was less reinforcing for him with holding the ball was less clear of a communication method for him than it was for Persi and I’m not really sure here that’s just one of my hypotheses.

So unlike Persi Madi’s extinction burst isn’t really best described through the number of false alerts made per repetition. When I kind of graphed out his number of false alerts per repetition, he was still making false pretty regular errors well into 60 or 70 repetitions out of about 125 repetitions that we did total, and Persi really just didn’t have as many false alerts after her initial extinction burst, which again was kind of in that 1920 range. However, Madi showed a very clear change in the duration of his false alerts. His first few for false alerts were 13 to 42 seconds, which was definitely longer than Persi’s in general, but nothing that had me really worried about this kind of attempt at waiting him out. But then we got to his 10th repetition, which was the last obsession to on day two. And this alert Madi really dug in and alerted for four minutes and 15 seconds, I figured that this was his extinction burst, and then his the section next day had no false alerts from it.

And that’s where I made a mistake, I got way too excited, and I pushed it way too far. Based on his experience, rather than basing my training decisions on kind of smart training principles. The next day, I expanded the search area to include a pretty large section of Camp rather than just our little training area. And that area was closer to the side of like a basketball court versus the size of like a racquetball court. This meant that Madi was now far less likely to encounter the correct target odor, and couldn’t really rely on other visual aids to clearly guide him on where to turn next. I use the same Scott as in the last repetition thinking that that would help because he just so easily dismissed it six times the day before, but I was wrong. His first false alert on day three was an absolute disaster. Madi went from sitting to laying down to rolling over on one hip, and then to my absolute horror and kind of Edwin’s bafflement, Madi started to doze off. And I really didn’t have a contingency plan for this. So we did ultimately interrupt the nap and end the training session there. I had a nice little cry, I thought about becoming an accountant or something. But at least I can say that it doesn’t appear that Madi was desperately frustrated by this false alert. I’d like to think that had he been really distressed I would have interrupted the false alert much sooner. So even though that long false alert was not at all my goal, I was really not planning on having to go through that, it appears that it did do the trick for the remainder of the 125 sessions. Most of Madi’s false alerts were two to eight seconds with just two alerts lasting between 15 and 25 seconds. So we had a huge drop off and alert duration after that. And then by the end of our third day of training, both dogs had gone through the worst of their extinction bursts. Although of course, we couldn’t have done that yet. And this is where I wish that I had had clear progression criteria for the plan. In many good progression plans benchmarks of success would be clearly defined to determine when to move up to the next step. We talked about – we heard this in the episode with conservation dogs collective and Auburn University where they talked about having 80% success at a given criteria before increasing that criteria.

And I really wish that I had done a better job of that with the ACK team. But after that fiasco with Madi’s 10 minute alert, we did take a step back, repeat it and repeat it a few more sessions with a variety of off target scats in the initial training area before hitting on another idea to help us kind of split out how do we start kind of expanding search area on increasing challenge without having another cause catastrophe like we’d had with Madi.

So I adjusted a bit creating a new search area on the other side of camp. So in the first search area, they were using kind of two liter bottles that were cut in half, and then buried partially in the sand. So you had these little pits of two liter soda bottles that Scats can be dropped into. So they were visually occluded. And the dog had something to kind of visually target themselves towards very clever, low budget option. But it made it really hard to expand search area because the dogs were kind of targeting those bottles. So I use some trash, rocks, sticks. And you know, whatever else I can find to make some little blinds for the scats, which eliminated visual cue of the bottles, and made it a little bit easier to kind of have these visual spots to check that I could move or kind of just build more rocks, rocks, structures to hide scats, or just kind of start being able to expand out our search area a little bit more systematically.

And again, I think this could have been much more systematic, but overall, our approach works pretty well. And I do want to mention here that at the same time as all of this, because these these sessions, were probably taking 20 to 40 minutes a day most days. And we’re doing this almost every day. But the dogs and handlers were also getting ongoing training in handling the dogs for expanded search areas where we were doing extended searches with just targets placed out and kind of building up that skill separately.

The handlers were learning about search strategy and odor dynamics and airflow and field safety and cooperative care and all sorts of stuff. And we expected all this training to ultimately combine really well. By building up on specific skills separately and then combining them ultimately, by this point, Heather had arrived. She was exhausted, she was jet lagged. She had I don’t know like 40 hours of travel on her way to Kenya but she put her gloves on and got to work right away with Edwin and we fine tuned our plan a little bit and I headed back to the US.

Heather continued working on expanding the dogs out into more realistic fields scenarios, the discrimination training and all the stuff I mentioned earlier. And then after a couple of weeks on the third co founder of K9Conservationists, Rachel, arrived in Kenya and she took things over from Heather.

K9Conservationists offers several on demand webinars to help you and your dog go along in your journey as a conservation dog team. Our current on demand webinars are all roughly one hour long and priced at $25. They include a puppy network all about raising and training a conservation puppy found it alerts and changes of behavior, and what you’re looking for teaching your dog a target odor. Find these through webinars, along with jackets, treat pouches, mugs, bento boxes, and more over at our website k9conservationists.org/shop.

So Rachel continued building on the expansion of the search area that Heather had done, and we were really working on bringing the dogs up to a more realistic field search, while maintaining this higher level of specificity. Rachel and Heather also did quite a bit of work on alert duration. So while I was in Kenya, most of the alerts that we were recording the correct alerts were very, very short. Rachel and Heather started layering back in the duration of the alerts, in order to a) ensure that we hadn’t broken the dog’s alerts. And luckily, it did come back very easily, and b) to ensure that the dogs weren’t basically guessing in another way by just alerting. And then if they didn’t get a click right away, they know that they knew they were wrong, and they can move on. So we wanted to kind of rebuild those alerts. And we did see that a couple times with Persi. As we started withholding the clip to build the alert duration, she did kind of hesitate a couple times, think about leaving the scat and we were able to kind of like, quick click for that behavior, which is not really what you want, but to avoid having her fully leave and have that experience, and then rebuild the alert from there. So that was really important.

And then when Rachel showed up, she started introducing handler movement. So at first, Rachel simply had the handlers hold a flexi lead and allow the dogs to move through the search area. She then started introducing movement and leash pressure from the handlers, we didn’t have time to introduce exercises like one that I know of called “Handler’s A Dummy,” in which the handler intentionally checks their phone at an inopportune time turns away from the dog moves away from the dog, intentionally kind of disengages from the dog or moves away from a true target or moves in a way that kind of guides the dog towards a false target. And the dog just learns to really trust themselves. Again, that’s not something that we did with the team. And I really wish that we had had time and we have communicated that to them since. But it’s you know, it’s always easier to do these things in in person.

Some other things that we introduced around this time were blind searches where we were layering in that the handler was unaware of the location or of the target or the non target. And we were kind of careful about when we did this because this sort of training is mostly for the handler. When dogs are still unreliable on their alerts. It introduces too much uncertainty to have the handlers also unsure of the correct answer. So until you can really trust that your dog is generally correct, you don’t want to not know whether or not they’re making the right choice. It would be like kind of grading a test and a subject that you were still learning yourself are still unsure of the answers on or still unsure of the answers on.

Once we did start to see consistently high rates of errorless repetitions we layered in smaller and larger searches, we layered in smaller and larger blind searches, Heather Rachel or I was always present to confirm the loads and support the handlers so these were always kind of single blind rather than double blind searches. Rachel also started introducing the dog to the concept of blank searches where there was no Scat present, this was really important to confirm that the dogs could continue to correctly ignore off target scats when there was no cheetahs Scat present. In real searches that a scats may be spaced so far apart that the dog can’t actually compare them. And then in small searches, it’s important to occasionally introduce the dogs to the concept that sometimes they’re not going to find anything, and then continue learning that in larger and larger areas. In the live searches handlers do generally plays gimmies to ensure that the dogs are going to make a fine, but it’s not always possible. And it’s best practice to avoid priming the dog to always make a find or particularly always make a find in kind of a specific amount of time.

So then Rachel finally also included multiple off target samples in a given search. So she introduced the team to searches with multiple off target scats teaching the dogs that may they may need to ignore multiple Scats of off target species before they got to encounter a scat of their target species. In the 18 repetitions that Rachel did where there were multiple off targets cats or zero cheetahs, cats, she, she observed zero falsehoods, so hooray.

So as we kind of went through our data analysis kind of post Kenya, I was really curious to see if different species or samples produce more false alerts for the dogs and kind of long story short here is there were a couple samples that gave us more trouble than others. Madi had the most trouble with leopard three while Persi struggled with caracal one. This is a little bit harder to kind of break out and actually understand though than it sounds at first. So for example, Persi had a 15 total false alerts regarding caracal one, but eight of those false alerts were in that single repetition where she had eight false alerts. So caracal one was just happened to be in use during her extinction burst, which happened to include really, really, with which happened to include a lot of false alerts sent and then you can also see in our in our data that there are no false alerts with caracal four, caracal five or leopard for which, you know, does that mean that those samples are magically better than the others? I don’t think so. My guess here is that those samples were used later in training. So they’re introduced when the dogs were already making much lower numbers of false alerts total. And those samples were acquired after implementing our new collection and storage protocols. So those samples were likely cleaner than new samples. They didn’t have any contamination of you know any of the sorts that we had talked about earlier dogs slob or anything like that.

But I suspect the biggest thing is that no samples just wearing us during the first four days of training when the dogs made the vast majority of their false alerts. The false alert rate was also broadly similar between leopard and care call scats, so there wasn’t a huge difference there. We did also want to look at handlers and see how that influenced our false alerts. So action for cheetahs in Kenya works on a six week on two week off schedule that ensures that the dogs are cared through throughout the weekends but handlers received some time off. This also kind of helps the handlers travel long distances between the field site and their home, which maybe you know, 1015 hours of travel during their off time, which obviously you can’t do that for a weekend trip. But you can if you’re getting two weeks off every so often. The point here being Naomi was off for her two week off period during the first half of my training protocol and missed the first 115 or 155 of the total 290 repetitions. So there was really no way to make a direct comparison between the handlers for early training, Naomi simply wasn’t handling the dogs while they made the bulk of their false alerts. Likewise, Edwin left for his leave during the second half of training and was not present for repetition 186 to 290. So it looks like Edwin was handling. So anyway, we can’t compare the handle and the effect of handlers on the dogs in this particular case, because Sure, Edwin was handling the dogs for 58 of their 63 Total false alerts or 92% of the false alerts. But that’s just because he was handling the dogs during their extinction bursts leading up to and after them. So next up, we wanted to make sure that all of this training all of this extinction had not made the dogs hyper specific.

Misses are a little bit harder to quantify than false alerts, as we talked about earlier. But both Madi and Persi hardly ever investigated the cheetahs got without alerting. What we did see is that nearly 20% of what we had coded as a miss was attributed to Persi on the second day of training, so I unfortunately no longer have video of this day. If I remember right. It seemed like the fact that we weren’t recording for the off target sample was kind of blew her mind and she was very confused at first and she was just kind of running around sniffing things and not alerting to anything a little bit on that second day of training. The dogs had lower miss rates with the oldest and most familiar scats. As well as the scats that were introduced the latest in the training protocol. Then the we have the highest miss rates with cheetah scat 14, 10, and 13. All three of those scats were newer scats to dogs but were acquired before implementing our new collection protocols. So nearly 60% of our total misses could be attributed to those three scats and most of those misses overlapped with Persi’s misses on May 10. The second month bumped in misses could be attributed to a change in search setup. But we were really excited to not see an increase in miss rate as we expanded the search area later on in training.

Overall, we felt really confident that our training reduced the false alerts for these two dogs and was not reducing the dog’s ability to generalize to new cheetah scats. In other words, we were able to increase the specificity of these dogs without necessarily losing our sensitivity.

Our last on day on the ground day of training with ACK took place June 16 2022, took about six weeks to implement this entire program. And since the completion of the project, ACK no longer really regularly does discrimination training with the dogs, they’ll kind of bring out these scats every so often do a quick test. If there’s a problem, then they will return to this plan. And if there’s not, they won’t continue hammering it. So they’re not exposing the dog to off target scats, almost every single training session almost every single day, which I think is a really good move. When I had last communicated with the team, the dogs were not really making ongoing false alerts in training or in fieldwork. But it’s always possible that these dogs could experience what we call spontaneous recovery. So we’ve reminded the team to stay vigilant.

So that is an overview of one case study one time that worked again, one time to improve discrimination skills in some dogs that were already struggling with this. And I hope you all learned a lot and maybe have some questions swirling around your head. So we’re definitely going to have to do kind of a listener Patreon Q&A at the completion of our discrimination mini series. And so we’ll stay tuned for that. And I’m definitely eager to hear any questions or comments about this particular protocol and see what y’all think.

As always, I hope that you feel inspired to get outside and be a canine conservationist in whatever way suits your passions and skill set. You can find K9Conservationists to hire us for training plans or training your dog or fieldwork or anything like that, or join our course or join our Patreon or any of those lovely things T shirts mugs, bento boxes, all at k9conservationists.org. We’ll be back in your earbuds next week. Bye!

Donate

Donate