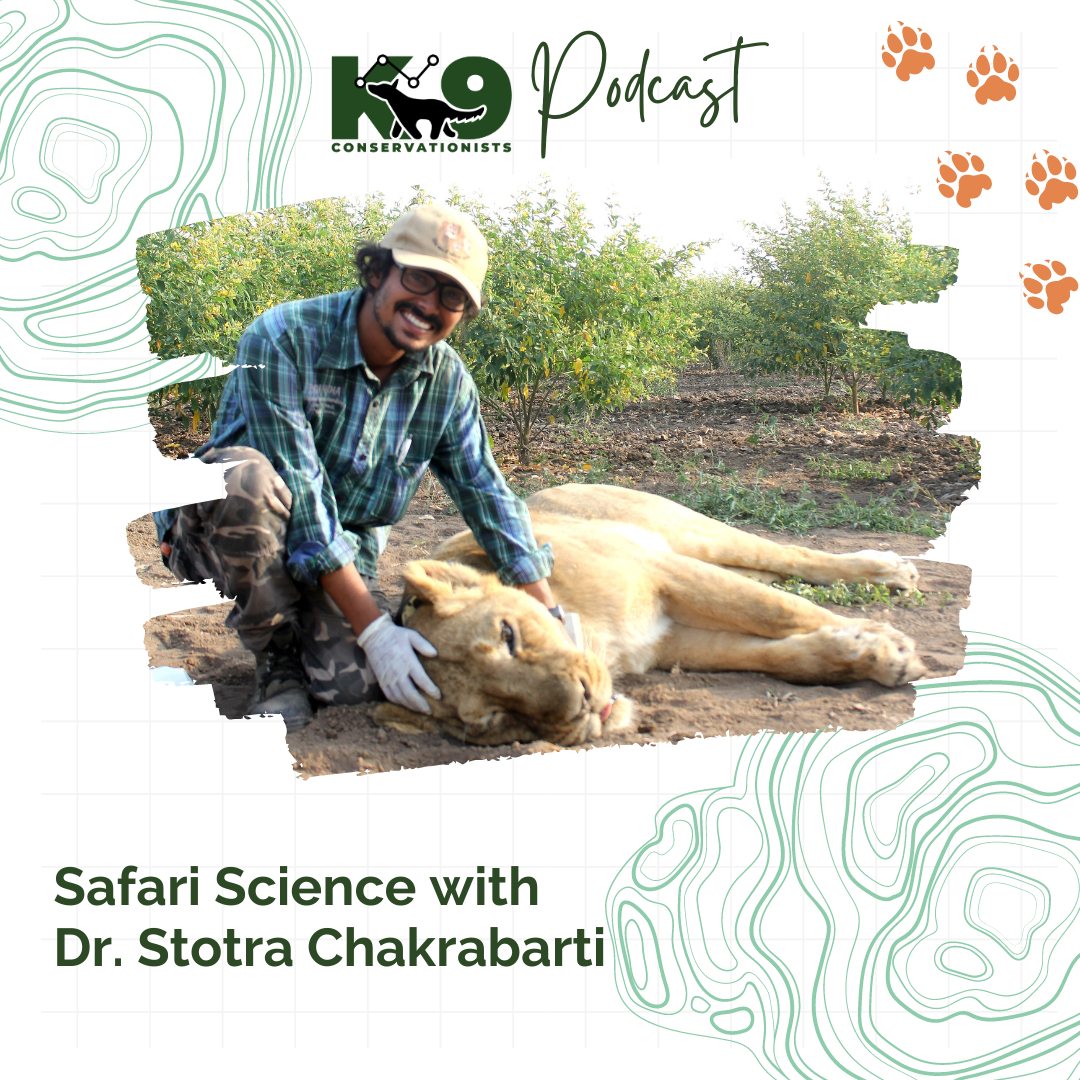

For this episode of K9 Conservationists, Kayla speaks with Dr. Stotra Chakrabarti about safari science and his experience working in the field.

Science Highlight: Faecal sampling using detection dogs to study reproduction and health in North Atlantic right whales (Eubalaena glacialis)

Links Mentioned in the Episode: None

Where you can find Dr. Stotra: Website

You can support the K9 Conservationists Podcast by joining our Patreon at patreon.com/k9conservationists.

K9 Conservationists Website | Merch | Support Our Work | Facebook | Instagram

Transcript (AI-Generated)

Kayla Fratt 00:10

Hello and welcome to the K9Conservationists podcast, where we’re positively obsessed with conservation detection dogs. Join us every week to discuss ecology, odor dynamics, dog behavior and everything in between. I’m your host, Kayla Fratt, and I’m super excited to be here with you.

Kayla Fratt 00:24

Today we’re going to be talking to Dr. Stotra Chakrabarti about safari science, his really, really interesting behavioral research with lions and much, much more. This podcast is going to be part of an another kind of unofficial series that we’re doing. I put out a call on Twitter a while ago looking for guests who would be comfortable talking to me about different experiences as field biologists and got a really, really amazing response. So this is the first of that.

Kayla Fratt 00:54

Stotra is from India, so he has a quite different lived experience as a field biologist from many of us listeners. Many of our other guests from this unofficial series are going to be queer, trans, people of color, and people of other differing backgrounds or ethnicities, and I’m really, really excited about it. And I’m really, really excited about this interview with Stotra to start us off.

Kayla Fratt 01:17

But before we get to it, we do have a research highlight to go through. So today we’re reading an article that again was summarized by our lovely volunteer Heidi Benson. This article is titled “Faecal sampling using detection dogs to study reproduction and health in North Atlantic right whales.” The authors are Rolland, Hamilton, Kraus, Davenport, Gilett, and Wasser, and it was published in the Journal of Cetacean Research and Management in 2007. So the question of this article was monitoring reproductive endocrinology, stress levels, disease prevalence and biotoxin. Accumulation in cetaceans is important in understanding the health of individuals and populations. However, it is logistically difficult to acquire acquire this data due to their large size and free swimming nature, which makes live capturing individual baleen whales for data sampling unviable. Because of sharp declines in right whale populations in the 1900s, researchers turned to fecal samples as a way to answer questions regarding whale health. However, this method was limited by low sample acquisition rates by human researchers. The authors of this paper wanted to determine if detection dogs trained on the scent of Right Whale feces will be able to find more samples in human searchers, leading to adequate numbers of statistic for statistical analysis, and better insight into the population of individual whales as a whole. So this study was conducted during August and September over a three year period of 2003 to 2005 in the Bay of Fundy, Canada, which is a seasonal feeding area for right whales. surveys were conducted on two separate boats. One boat had a detection dog handler, driver and research and data recorder while the second boat had a crew of six to eight folks conducting standardized right whale photo ID surveys that collected feed fecal samples opportunistically sent training took place over nine days, Heidi writes, which seemed short to me and was refreshed for one to two days prior to the start of each session season. Two dogs were used alternately in 2013 2004, with only one dog used in 2005. And Heidi again notes that’s not standard why that happened. So surveys with dogs were done via transects running perpendicular to the wind downstream from right whales, or areas previously used by right whales. Dogs are a position on the bow of the boat and the dog handler directing the boat driver to where to go based on the behavior of the dog until the sample was located and collected. Service with dogs were not conducted when winds were higher than 10 knots. Sampling efficiency of detection dogs was then compared to opportunities, opportunistic sampling of research human searchers, but only on 19 days when both were working simultaneously to control for weather variability and whale densities. That’s smart. detection dogs found significantly more samples in humans data across all years, overall from 2003 to 2005. Dog searches resulted in 1.1 samples collected per hour, while opportunistic human searches resulted in 0.25 samples collected per hour. In other words, dog efficiency was over four times higher than opportunistic human searchers. Dogs also had a higher estimated detection distance of up to 1.93 kilometers and found samples in areas where whales were not observed nearby, increasing the total area that was sampled. The authors conclude the paper by stating that detection dogs can quote dramatically increase fecal sampling rates from free swimming right whales and quote and note that such surveys could be used for monitoring the health of other important marine species such as bottlenose dolphins, sperm whales, blue whales and more.

Kayla Fratt 04:41

My only note from from this from Heidi’s before we moved on to the limitations here is that nine days doesn’t seem super long, super short to me for actual sent training, but I’m wondering how long it took for them to get the dog teams used to the boat. Not sure if it seems super wise to me to just do training with the dog and then throw the dog handler team on a boat. And I’m wondering if these dogs had previous experience doing other whale surveys, so that them and the handlers and the drivers all could actually work together as a coordinated team because that, to me seems like the hardest part, especially if you’ve got an experienced detection dog. So as far as limitations go, the authors note, “The success of this method dependent on the involvement of a professional dog trainer and experienced handler, and dogs and a boat driver with intimate knowledge of local tide and wind patterns. It also involves the use of dedicated vessel for detection dog surveys, because of methodological conflicts between visually based photo ID surveys and detection dock server protocols and quote, highlighting the fact that in addition to having a highly trained dog and handler, which is the minimum for many projects, this specific type of endeavor, requires more human experience and that it needs the knowledge of a lot, a local boat captain and access to more equipment, ie another boat, which adds several layers of logistical hurdles.” And he adds and I love this sounds worth it. It’s cool, cool as heck study. And yeah, we really appreciate that. So again, that was the article “Faecal sampling using detection dogs to say reproduction and health in North Atlantic right whales.”

Kayla Fratt 06:18

And without further ado, let’s get to our interview with Stotra. Well, thank you so much for agreeing to come on the podcast, Stotra. Why don’t we start off with, you know, introduce yourself? What do you do now. And we’ll go back into your history a little bit more in a moment.

Sotra Chakrabarti 06:32

I’m super excited to be here. Thank you so much for inviting me. I’m Stotra. And I am a faculty at Macalester College in the department of biology. And I am a behavioral ecologist, or an animal behavior research scientist by training, and I, I study animals, I study behavior of animals, and I also teach about them. And typically, I mostly work with large carnivores, lions, tigers, wolves, large mammals are a sort of my speciality. But it’s more or more often than not the questions of fundamental animal behavior, as well as how these animals live with the communities that like human communities that share space with them. That’s sort of the drive of me and my group here at Macalester.

Kayla Fratt 07:22

Very cool. And so why don’t we go back a little bit. Honestly, reading some of the papers that you’ve written and some of the stuff that you’ve done. It’s what, you know, what many of us who grew up wanting to be biologist wanted to get to do so, what were you like as a kid? And how did you actually manage to get into get into this field? So successfully, it seems like.

Sotra Chakrabarti 07:42

Well, that’s thanks so much for that question, because that just gives me a little bit of like time to reminisce about childhood and growing up. So I grew up I grew up in, in a rural semi urban gradient in northeastern part of India, in West Bengal, right in the foothills of the mountains, Himalayas. So while growing, so traditionally, we’re growing, I literally come from a place which has a lot of wilderness, which is adjoining to the place where I was growing up. So leopards, and wild elephants were frequent neighbors, right? So I was literally growing up watching these animals and getting smitten by them this nothing like watching a leopard or like, elephant herds of elephants passing by, right so as a kid, I was growing and getting smitten by them. But it was not just that, I was also have had the great opportunity and fortunate to have had fostered and rehabilitate rescue animals, right from birds of prey to leopard cubs and jungle cat kittens. My parents were not happy that they will always had one other wild animal at home or their son is trying to, you know, having a having an owl in the garage, there’s always that kind of like an up and down at home.

Sotra Chakrabarti 09:13

But then my parents, my family has been super supportive about this. So so as you can, as you can understand that I was growing up, literally feeling and touching and like being around animals, it’s very easy to get smitten by them. But I was also growing up in a setting where my my cousin brother, who practices rural medicine does not, did not turn up for dinner one evening because he was treating one of his patients who got mauled by a leopard that same day, right. I was also growing up in a in a setting where wild elephants broke the neighborhood boundary wall because the jackfruit tree was fruiting in that alleyway. So, on one hand, I was growing up being smitten by these amazing animals by these amazing critters, but I was also having a reality check what what these animals can do in to human life and property. So that sort of spurred the ecologist that I am today. So I kind of asked questions about animals, and how that can facilitate how these animals and we can sort of coexist in the Anthropocene.

Kayla Fratt 10:31

Yeah, that’s, that makes perfect sense as far as why you were so interested. And I can, yeah, I can imagine your parents and my parents might have some stuff to talk about, as far as having the kids that bring stuff home. I generally, it was more like raccoons that found their way to me. So potentially less consequential.

Kayla Fratt 10:48

But yeah, and one of the things that I’m really hearing them one of the things I’m excited to talk to you about more here is because you grew up in an area that actually had a lot of the animals that you grew up to study, you have a lot more of an understanding of what it’s like for the communities in these areas. And, you know, how that informs your, your career as a conservationist. And as an ecologist, is one of the biggest things we’re here to talk about today. So how did you kind of go from, you know, being this kid who, you know, a saw some of the challenges of being alongside these large animals, but was also really enamored with him to actually end up being a professor at Macalester, that can’t have been a short, simple transition.

Sotra Chakrabarti 11:37

I think so. So I, I literally, as growing up my own, really wanted to be a soccer player that didn’t quite take off that didn’t quite launch. And the next thing that I really was interested in was animals, as I just mentioned, and I pursued zoology in college, because that was something that was related to something that I was super interested in biology and like organismal, biology. Most of my cousins, most of my siblings, most of my family members of my cohort, they’re all either doctors or engineers. And that’s typically the major profession in our in our sort of the socio cultural background that I come from, because that’s, that’s the route that people take mostly. And I was like, not enough. We have enough doctors and don’t want to be a doctor, as a medicine practitioner, I think.

Sotra Chakrabarti 12:40

And so I ended up doing zoology in college. And then one thing led to another, and the Wildlife Institute of India, which is the only federal institution that does wildlife research in the country does a master’s program once in every two years, which is supremely competitive. And I’ve worked really hard, but I also got lucky to get a position in that course. And I got a scholarship, got a position, started doing it.

Sotra Chakrabarti 13:08

And that sort of got in, got me into like, like, you know, moving on transitioning from like, natural history, to actually objectifying and trying to understand the natural world in a far more regular, rigorous and a more direct sort of way. And since then, like meeting, meeting, networking with professors, networking with actual real time scientists made me really interested in understanding animal behavior. And carnivores are, are a group of animals that I was very interested in it also, they also come with their own challenges of coexistence, because I think they are one of the major threats to human life and property. And that’s something that I grew up with having leopards, and dangerous animals in our backyards also bring that sort of looming thought, and it just made my, you know, sort of professional outlook far more meaningful, that this is something that I could relate to and connect with. Because those were values that I was growing up with, like, hey, this, this is a challenge to live with dangerous animals, like why not study them to make like to see how we can better better understand that sort of coexistence.

Sotra Chakrabarti 14:26

So that happened, and then I started studying Lions for my master’s program and then continue and since then, I have been studying Asian Lions for the past 12 years and diversify to other carnivores to African lions, to voles and doing some elephant work. So, so yeah, so it has been more of like, transitioning from those fundamental understanding of questions of like how animals behave to how that and sort of support or promote coexistence?

Kayla Fratt 15:06

Gotcha. Wow, yeah, that seems like such important work. And again, it just, I have not had the opportunity to connect with a lot of, particularly people in kind of the International, big, big carnivore world who actually grew up there. And I think if you spend enough time in this world, most people start to understand and even especially if you’re living, or spending extended periods of time in country doing fieldwork, you start to understand, but I do think there’s something very different about growing up and having experienced it.

Kayla Fratt 15:35

So as what we’re going to kind of do today, this is going to be slightly different episode from how we normally structure things. But I want to go through some of your research and use that to highlight the importance of and how potentially to do well, some really important things when we’re considering especially international conservation work, or even just going into communities that are not kind of your own. So I wanted to start out with a couple definitions for our folks at home. And honestly, for myself, to get to make sure we get everything squared away. So why don’t we start out with parachute science? Is that a term that you use? And what what does that mean to you?

Sotra Chakrabarti 16:14

Yeah, so parachute science, or helicopter research. And there are other talents about it as well, like parasitic research or even Safari study is typically when, you know, researchers from more resource to countries are wealthier countries go to developing or countries or places non native places, which are not as wealthy or not as rich, as full of resources to collect information, or data, or samples, travel back to their own, then travel back to their own country, and then analyze the data, published the results with or no involvement with local researchers.

Sotra Chakrabarti 17:01

And what happens with this kind of a practice is basically it undermines the role of local communities in ecological knowledge, which kinda is a, which is a slippery slope in itself. Because then typically, what happens is that that creates a straighter or a system of power dynamics, it also creates a system of probably not a holistic understanding of the ecosystems or the systems that the researchers are studying, because people who are local communities who have been living there for generations have a far better or far more realistic understanding of that for that particular place. And so that’s that’s basically is a complete should be a complete nono for inclusive research.

Kayla Fratt 17:54

Yeah, definitely. And I’m excited to get a little bit more into some examples of what what it can look like to do this well, and to avoid this. We don’t necessarily need to give examples of what what it looks like to, you know, be a parachute scientist, or do I love the safari science? I haven’t heard that one before. I think that that evokes the right image. So how does this again, I know that this question could be multiple books. But how does this kind of relate particularly to colonialism?

Sotra Chakrabarti 18:28

Well, I think, if you, if you think, if you just take a step back and think about colonialism as a definition, it would be like a practice or a policy of like a complete political or socio-political control over a place, it can be a country, it can be a unit of administration, and occupying it, and also exploiting it, either economically socio culturally, or a combination of everything, right. So that’s basically what you can think about as a definition of colonialism. And if you thinking about parachute science, it’s sort of it’s a sort of a new colonialism, right? Because there are, there are people or their organizations or their agencies from a different part of the world, which comes collect information, collect data from a particular place, which is not native to where the researchers are from, and then collect data and like, scoot away. Right? And so that’s the underlying exploitation of information here off of understanding of both actually knowing the system in a way that that local communities know that that exploitation is basically where the where it links, the colonialism, the new colonialism and the practices that we have right now as Is parachute signs.

Sotra Chakrabarti 20:01

So that’s sort of what we’re talking about in terms of like the colonial bridge, or the colonial sort of the undoes underlying colonialism in data and practices and research practices at this moment.

Kayla Fratt 20:21

Yeah, that makes sense. And it’s, it’s so fun. You know, I can tell that you’re a professor and I can kind of start seeing some of these things linking back together to, you know, discussions that I had, as a student as well about, you know, like, what is wilderness and you know, who even has a concept of what wilderness is and how that is, you know, separating people from this from the land in a way that? Yeah, I don’t know, I might be making too many different jumps and connections here for the for the podcasting medium. But yeah, I think I think I’m still following and I hope that means that everyone at home is following as well.

Sotra Chakrabarti 21:03

No, I absolutely would jump in and say like, yes, what is wilderness and this entire idea of the pristine version with in all our brochures and like, there is like, fantastic. Open landscape, there are elephants out there, but there is no presence of humans, or people. So yeah, and the whole idea of like, are we part of nature, or it’s like, who, who brought about this idea of pristine wilderness. That’s a very western concept. And that’s a very broad. And it’s a very important concept, right?

Sotra Chakrabarti 21:40

And I’m talking about so I come from that part of the world, where we have been talking about sanctuaries, in in 300 BC, we are talking about appearances, which are basically, which are basically protected areas, but which have interactions of humans and biodiversity where humans and biodiversity both coexist. And there are rules of how to make that coexistence in the best possible way. It’s not the idea of fortress conservation that we have right now. The whole western, new Western philosophy of like fortress conservation, were people out protected areas, of course, I’m not undermining protected areas at all. I’m just, I’m just questioning the narrative that led to the formation of current Protected Area thought, as a as an additive.

Kayla Fratt 22:44

Yeah, yeah, exactly. And I know, that was something I thought about a lot when I was proposing a Fulbright to go back to Kenya and looking at you know, most of the research that I was able to find, that was trying to build my proposal off of was all in national parks, which are, you know, kind of the highest level of protection in most countries, and almost very rarely have people who are permanently inhabiting the area. And I was hoping to be working in a community conservancy, which in Kenya, or these kind of managed multi use lands where we were going to be working directly alongside and with, you know, the local semi nomadic herders and, you know, hope we were hoping to try to design this in a way that ultimately the data that we found could be useful to these folks as well. Or at least, you know, ask, ask them what they thought about a lot of it.

Kayla Fratt 23:35

So, you know, this is kind of where a lot of this stuff started coming up. For me, I think when I was primarily doing research in the US, and you know, if most of my fieldwork was, you know, doing bird and bat mitigation on wind farms, I wasn’t as spending as much time worrying about colonialism, and how we were conducting our research. And then as soon as we started going to Kenya, and then we just did some work in Guatemala, and now it’s starting to be something that, you know, I’m personally trying to make sure I educate myself on and, and also just make sure that we talk about a lot for folks who maybe aren’t doing this sort of work yet, but are looking at what we’re doing and think it looks really cool. Okay, great. Well, let’s, let’s talk about things that we need to be thinking about as we go forward with this. So, yeah, do you have anything to add there?

Sotra Chakrabarti 24:23

No, I think, I think it’s, it’s this this entire process of like learning as we as we experience it, there, like we have lived experiences and then, like networking, or connecting with people who have had lived experiences just to be a better informed researcher is the way forward because I definitely think that we cannot have like lived experiences, supremely important, but then we can only have so much of lived experiences, but that’s where collaborating and networking comes into the picture.

Sotra Chakrabarti 24:58

Right, you meet, you are being cognizant of the fact that there are people on the ground on different parts of the world who are working in different systems who have, who have different kinds of knowledge that they bring on the table local communities who have been living there for generations. And we have like and collaborating with them, collaborating with them in the most efficient and the most inclusive way possible, is the way that we can have responsible research, research that is important, not only from the search for knowledge or for signs for the sake of science, but also for communities who are living right there in those places. So I think I think that’s the way forward right response, doing not just good research, but also responsible research.

Kayla Fratt 25:57

So, yeah, yeah, definitely.

Kayla Fratt 26:02

K9Conservationists is thrilled to offer a self-study online class for those interested in joining the field of conservation dog professionals. This course includes 18 modules of video lecture assigned reading homework and quizzes. We have lectures from 10 amazing guest instructors, including “Fostering Motivation and Joy through Hide Placement Training” with Laura Holder of Conservation Dogs Collective, “Safety Training and Assessments of Dog Teams” with guests Fiona Jackson and Tracy Litton of Skylos Ecology, “Special Considerations for Insect and Plant Training Samples” with Arden Blumenthal of the New York New Jersey Trail Conference, and “Building Networks, Acquiring Clients” with Paul Bunker. Our alumni group is active and supportive. And we welcome students of all levels and backgrounds. The course is priced at $750 with generous financial aid and discounts available for Patreon members. Learn more and sign up at k9conservationists.org/class.

Kayla Fratt 26:53

So I think now’s as good a time as any then to pivot into talking about some of your recent research, because you have you sent over some very, very interesting papers on Behavioral Ecology that were a lot of fun to read. So why don’t we talk about some of the research you’ve done through the lens of kind of inclusion? And you know, what, what you did to ensure that the community was involved from start to finish? Or you know, where they could be and where it made sense for, for your research?

Sotra Chakrabarti 27:24

Yeah, that’s a great question. And I’ve been reflecting upon that a lot, because I think I am still working progress as we work through this. Like I am getting more sensitized, more educated, more learning more stuff. So I’m only reflecting about how things have been before.

Sotra Chakrabarti 27:43

But I definitely think that while starting off, doing my graduate research, both my masters and my PhD, since I’ve been selling lines, and one of the major, one of the main questions that I have sort of pursued is to try and understand mating strategies in Asian lions. And that’s something that was that came to that that idea is, came to me or basically was born out of interactions and, and communications and conversations with local communities, because people who live in this particular place have been living with lions for the past 200, 300 years. And so they have been observing animals for so long.

Sotra Chakrabarti 28:33

So of course, it it was important for me to actually understand what they knew, before trying to get into the picture of like, okay, asking questions, because I think these would be the questions, right. So I when I went and started studying lions, I went in with a thought process of what we know about lions that comes from these quintessential like, you know, African Serengeti, like Tanzania and play parks of Serengeti Ngorongoro, where there has been like such pioneering long term research that has been done, and I went in with that kind of thought process of like lines or lines, right, so they will be there. But then when I went there, went to gear, which is in Gujarat, first of all, I did not know the language. And so I took, I really was motivated to learn the language. So I really learned I started speaking the language, like understanding it in like three months because it’s near to the kind of language that I speak, but then started speaking the language pretty fast after that as well.

Sotra Chakrabarti 29:48

But what that helps me was to basically communicate with local communities and they did not have to translate what they were feeling. They were exactly talking the way they You were feeling which makes a whole lot of difference when you’re actually communicating about different things. And so what we know of classic lion biology coming from like these pioneering studies done in Tanzania, is that you know, there are lions are he egalitarian males have coalition’s that are pretty much they don’t have dominance hierarchies females are also egalitarian in their groups and males sort of monopolize reproductively monopolize the females in their group. So it’s like a group of males sort of monopolizing an entire pride. And that’s what we know.

Sotra Chakrabarti 30:43

But when I started talking to local communities, they were pretty much like, no, there are like females have multiple partners from different groups, different male groups. And I was like, Huh, that’s interesting. So I would say, and that’s what we basically went and investigated through my PhD, and we came out like, hey, females are promiscuous, they have multiple May, male partners from different, you know, different rival male groups. And that sort of confuses paternity, which is a very win-win scenario for females. But that sort of idea actually came because, first of all, we had a long term project. And we had information that we could back upon and rely upon, and we were looking at these pedigree and all that, but also, because we were like, I could manage to go and chat with local communities, our field assistants are from the local communities belong to those communities. So we could chat. And basically they were saying like, Yeah, this is this is sort of things that are we are observing, we have been observing, and that sort of molded the kinds of questions that I asked.

Sotra Chakrabarti 31:56

So I believe that one of the ways in which we definitely can sort of safeguard against parachute signs is like, if researchers from different other places go and work, it is important to understand or at least make an effort to learn the language, it will not happen overnight. But we have fantastic tools right now to learn new languages. And that just opens up an entire world of understanding of the system. Because there’s so much lost in translation, that it’s just too difficult to fathom. And especially when you’re talking about the natural world, where there’s so much a feelings and vibe involved, right? Local communities will not be able to translate how they feel, or what’s the vibe, like. So it just does not happen. So if you can learn that, like that’s, that’s not the That’s not like you learn the language done and dusted. That’s, that’s all you have to do for avoiding parachute sense. No, that’s one of the steps that you do.

Sotra Chakrabarti 32:58

And then, like, I, I always like, I think my field assistants, our field assistants are the are my mentors in the field. They are, each of them are worth eight or nine PhDs themselves, because they have been working with PhD students. And they have had these PhD students happen under their mentorship. And that’s why it’s, it’s very important for me to acknowledge what they have brought to this particular project. They are collaborators, and they are definitely one of the br the major pillars for taking, making this project a success, or at least trying to understand our answer those questions about very fundamental line behavior. And, yeah, so I think those are some of the ways that I was mindful of not indulging into parachute science, because I also say, I am an outsider to the system, because I’m not from that particular state. But yeah, so it’s, it’s, those are, I think, some of the ways in which I felt that it made my research far more responsible and far more holistic.

Kayla Fratt 34:25

So yeah, yeah, no, that makes perfect sense. And that’s, you know, I, this is such a small minor example, but it’s the only one I can really think of, but, you know, one of the things we run into in Spanish with big cat research is that people will call Jaguars Deaconess, which will directly translate to Tiger. And if you’re not used to that, you know, it’s very confusing and kind of upsetting the first dozen times you hear it, but that’s just that’s just what the local language is going to be and getting used to the fact that they don’t mean to, you know, They don’t mean Tiger, they’re not confused about the difference between a tiger and a jaguar. It’s just a linguistic thing.

Kayla Fratt 35:07

And, you know, I, one of the things I’ve been spending a lot of time thinking about lately, because I’m living somewhere where I’m speaking Spanish all the time, and my Spanish is very good, but it’s not as good as my English is the the amount to which imperfect language makes you feel less intelligent than you are, and makes other people think that you are less intelligent than you are. And I think as researchers coming into communities, it’s important for us to be the ones who are maybe on that backfoot and trying to figure out how to communicate. Because I think it makes it much harder to dismiss what someone else is saying. Or, you know, really trust what they’re talking about when I’m trying, I’m not sure if I’m explaining this one, but it looks like you’re nodding. So maybe you can paraphrase or chime in and help me out?

Sotra Chakrabarti 35:59

Oh, absolutely. No, I think I am. Like, I get what you’re trying to say. It’s like, Yeah, you like, if you are sort of, like coming in with that upper hand off like I this, I know more about that system that just puts you into that sort of an unconscious bias of not letting Yes. Not letting like community or the traditional ecological knowledge flows through you, because you will be at keeping everything. Like you will be talking against all of that, because you’re not trusting that. But if you come in with that, sort of because as you’re saying, like not knowing the language is are basically struggling with a language is a very humbling feeling. And that sort of humility is very much needed for us responsible science.

Kayla Fratt 37:01

Yeah, definitely. And I guess yeah, maybe to stick with the tigray example. Like, I think it would be much easier if someone said, Oh, watch out for the tiger as I’m in the Guatemalan jungle, I would be like, okay, this person just clearly doesn’t know what they’re talking about. I’m going to totally disregard what they’re saying. And yeah, I would have this this bias, but as soon as we’re speaking Spanish, and I’m the one having to be like, Am I understanding him correctly here or her you know, it helps just I think increase that credulity and really increase your ability to interface with with the local with locals on so many other levels.

Kayla Fratt 37:36

So, the other the other example that I was hoping we could kind of talk through, as we go through some of your research is about field safety. Particularly, I think if you’re kind of like a swashbuckling six foot two white guy, there are some aspects of field safety that everyone needs to think about, you know, as far as like snakes and elephants, honestly, you might be at higher risk if you’re a six foot tall white guy because of your lived experiences with some of those things. But there are other things that are going to show up differently depending on who you are in the field. And I don’t know if you have any stories or examples that we can explore there.

Sotra Chakrabarti 38:18

That’s a great question. And all in all my years of working with animals that are that are amazing, very charismatic and beautiful and also very overwhelmingly dangerous. I think in I think I have my my field safety or like, all the all the all, every time I have felt uncomfortable, or like it’s been like, like a sticky situation. It is all it is. It’s barely been from like animals. It’s always been associated with humans. And and I’m not like a six foot two, a barely 5’5″, 5’6″. And, and I am a person of color. And and so I guess there are differences in how in navigating the field and navigating field work.

Sotra Chakrabarti 39:19

So Well, I would say that I can quote a couple of examples. So I think this was during fieldwork when I was tracking following one of our radio collared lionesses. And this is basically again a time when we are doing these 24 hour continuous monitoring sessions where we are following a radio tag line line and the group members are 24 hours a day for at least somewhere between eight to 15 days so there are two teams. Three people in each team I always took the night shift. So it’s like five in the evening to nine in the morning and from nine in the morning to five in the evening. So it’s like we’re just continuously following them writing down all behavior, whatever they’re doing, it’s, it’s all behavior sampling throughout the time wherever they’re moving. So one of our radio collar and this was one night, one of our radio collared lionesses went into a village settlement. And she and her two sub adults during that time killed three livestock, people who are not happy, of course, right? People don’t well, while the good route people are far more tolerant towards losses towards love from large carnivores like lions, but still its livestock, their major economy being at risk, and it’s not an easy feat to live with large carnivores, it’s dangerous.

Sotra Chakrabarti 40:52

So, and this was three in the morning, and I and the entire village is up in arms of like, you know, they are really mad, because they have just gotten three, like a person got three of the major economy economic unit got killed, right. And it’s, I, we were in the middle of it, the people are not happy, and the crowd was like, they are trying to blame someone, and they are not, they’re not blaming the lions. They’re blaming us, because somehow they connected the reader color with the research. And that’s, that just completely blew out of proportion. And it was a very scary moment. Because, you know, it’s there were lots of threats and everything being passed. And the only thing that led to me, sort of every time I think about this, this incident, I get like goosebumps, I’m like, oh, that day that night, I am so lucky to be like, you know, my, my car was not smashed or something didn’t happen to somebody, all of that.

Sotra Chakrabarti 42:12

But I think the only way out that we’ve like, the only thing that helped was like I had my field assistants and all of us could speak the local language. So we were all speaking to people. We were all communicating. I’m like, Listen, this is what’s happening. And this is why we are here. And we are not part of this. But tell me what your allegations are. We can take it to the state government to get you compensated. We are on your side, this is what we are doing. But we were speaking in the local language. And that sort of reduced a lot of tension. Right. So that really helped.

Sotra Chakrabarti 42:51

So I think I think that was one of the closest calls that one very similar incident was one of our radio collared lions killed a boy. And things just blew, like, again, it’s it’s crazy. And it’s tough. You know, it’s just how do you how do you prepare yourself for something like that? Right? Like you are one fine morning, I’m going to monitor some other line group because we monitor these radio collared lines, like in regular intervals, I get a phone call, and this was like, this was Christmas. I think 2015 And I get a call saying like, Hey, your radio-collared lion has killed some kid, and the translation, the loose translation in the local community, in the local language, I felt that it was like the lion had killed a cop. And I’m like, there are no small cops in that area. And this person goes back No, no, not a car, a human child. And I’m like, okay, and then scooting back in. It’s, again, talking to people. Just like people are coarse mad. It’s tough living with large animals and such dangerous animals.

Sotra Chakrabarti 44:19

And I think the only way I have gotten out of these really scary, really difficult situations with people is that we could speak the local language. And that has really, really helped me to just communicate in their language so so I think that and coming back to other local like fieldwork safety and that this is something that I teach in class when I’m teaching the courses that I did, like such as wildlife monitoring, because I think being a person of color in an in a mostly a white world world, a also with a very different kind of a weapon culture or a gun culture. Then the kind of place that I come from, it’s very difficult to reconcile with that.

Sotra Chakrabarti 45:04

And it’s it’s that that internal shakiness and like, you know, pull backs of like, I don’t know if I will be safe in the field or not. And there are so many stories out there, people have lived experiences of guns being drawn at them or, or, or bullets being fired. So yeah, it’s just make the whole it’s just makes fieldwork quite an accessible to a lot of different people having very different, like having different kinds of identities.

Kayla Fratt 45:41

Yeah, definitely. And, yeah, I’m glad that we brought up the language thing so many times, and in so many ways, and I think, you know, one thing, you know, people in the conservation dog world, you know, we tend to do a lot of contract work, a lot of short term work, where it might not, night might not be reasonable for us to be able to pick up the local language everywhere we go. But at least we can have fields, text scouts, you know, our orienteers something being local.

Kayla Fratt 46:10

And, you know, I was really amazed I’ve, most of my travel has been in Spanish speaking countries where, you know, I’ve been speaking Spanish, quite fluently for over 10 years now. But when I was in Kenya, you know, just learning how to say, thank you. Good morning, what’s the weather like, you know, really, really basic stuff goes are pretty far away, if that’s all you’re able to do. And one of the things I was really thinking about in the livestock story as well is just having an understanding of what a cow or a goat or a sheep means to that family. Because it’s not, you know, just a cow, or just a goat or just a sheep or whatever, it was the same way. And I don’t know what it’s like in India, but you know, in Kenya, like cattle are quite literally currency.

Kayla Fratt 47:02

Yeah, it’s an even growing up in a farming community in you know, Wisconsin, where there was there was a ton of emotion and a ton of very, very important financial realities around livestock, it’s, it’s still just not quite the same thing. And your, your understanding of that, I’m sure helped the situation a lot.

Sotra Chakrabarti 47:20

I absolutely, I absolutely echo your thought it’s like it’s currency, and fam their family members, they there is an there is like a, like a, like an economic Bond. Bond, but it’s those also like a personal bond to the, to these animals to domestic animals, right? We feel strongly about domestic animals. And, and they do too, and we all do, and it’s a huge loss. And, like, what I feel is, like, knowing that the language made me sort of understand the pain and the reality that people were going through. It’s not just as you said, it’s not just a cow or a buffalo. It’s a loss. And that loss, comprehending that loss was difficult.

Kayla Fratt 48:15

Yeah, well, so then, as we’re wrapping up here, you know, you mentioned that you teach a class on field safety and inclusion, I was wondering, you know, what things maybe come up in that class that we haven’t covered yet in this discussion?

Sotra Chakrabarti 48:30

Well, so the class so I teach, wildlife monitoring techniques, and I also teach animal behavior. And both of these classes like we I have a very strong sort of, like presence of like, what it is to be like a field researcher and like one of nuances that you have to consider, or what it is to be a research and responsible research a few things other than, like field safety, you’re talking about, like what, what are the things they might or my students might sort of come across in the field talking about different lived experiences, I bring in guest speakers from different parts of the world without basically like friends and colleagues and collaborators who have worked from smaller birds to marine dogongs and manatees and very different, very separate disparate experiences, different career stages, and based on their conversations and different gender identities, and based on their because, because I can only speak to some of those because I get I have only have had only a component of those lived experiences, right?

Sotra Chakrabarti 49:42

But then, with bringing these guest speakers, I can provide my students with role models that they can follow beyond me and others around here. So that’s one thing that I that I do, and that has been a strong focus of my class. are also the other thing that I have been doing is like we read papers, published papers. But I’m also like one of the things that my students have to do is to go and research the researchers themselves. It’s not just the science, but who’s doing the science. That’s also important, right? And that’s something, I think all my students have mentioned that like, Oh, this is the first time this has happened, like, we have been told to, like, we mostly read papers we’re talking about, we are critiquing the science, or we are looking into the research, what the research tells us, but I’m like, Yes, that’s great. But let’s take a moment. And that’s additional incentive for them. Like, hey, if you do this, you get, like, I start getting the ball rolling by giving them incentives, and then it’s like a practice.

Sotra Chakrabarti 50:51

So there, then they are going and finding out what the what the researchers are doing what the researchers basically outlook is. And they have written fantastic essays about not only the research, but also about the researchers and how that sort of connects the whole whole outlook of that particular research, per se. So I think that’s something that has been one of the most rewarding moments for me, when I read those essays from my students that students have actually gone and read.

Sotra Chakrabarti 51:26

And we’ve had fantastic, wonderful conversations about about the perceptive conversations about these also, a few other things that I that we also talk about is how to responsibly use different kinds of technology that you put in camera traps. What are the kinds of ethics that you’re going to use are going to follow? Are you going to, are you gonna report any illegal illegal activities? Is that in the purview of your research? Right? That kind of perceptive conversations, because I think it’s very important to have those conversations right away. Because if people are going to get into a career of following this profession, then people should be aware of what they might be encountering.

Sotra Chakrabarti 52:18

And as I say, and I, as I tell them, every now and then, that probably the animals and the wilderness, although it’s a very dangerous place, if you are going to work in the wilderness, it’s a supremely dangerous place. Because it’s overwhelming, it’s powerful. It’s difficult to think about that kind of power, right. But also, the animals and the plants and the trees, they are not the only dangerous things probably that you would encounter. They’re associated different other problems and considerations of safety. If you’re in the middle of somewhere, and you don’t have anybody around, you probably have to keep the safety rules in place. So those kinds of thoughts were so yeah, so I think I think that’s something that I have been, that I’ve been very strongly invested in, in my classes, and that has resonated quite well.

Sotra Chakrabarti 53:22

And I think, and I am just by conversing and communicating and talking to a lot of different people, including you right now I am set like, you know, evolving, bringing in new or different thoughts to make it a far more inclusive, more approachable and accessible courses over the air.

Kayla Fratt 53:48

Yeah, well, and it’s truly amazing. To me, it’s how I graduated college in 2016. How far this conversation seems to have come even in that, I guess it’s seven years, like it’s not nothing. But you know, I don’t remember really talking about this from the lens of field safety in my undergrad courses, and we did talk about field safety.

Kayla Fratt 54:13

But yeah, and I really love this idea of, you know, looking into the researchers as well that’s not something that I did in undergrad Yeah, well, is there anything else on this topic that you know you wanted to circle back to or expand upon or that I forgot to ask you about before we go.

Sotra Chakrabarti 54:29

Well, I think the one other thing that I also mentioned which I know might be a completely side point is it’s it’s probably it’s a good heads up to every researcher that yeah, it’s it’s a it’s a tough field. I guess the real it’s, it’s more or less like we are overworked and underpaid all our lives probably. But it’s like it’s getting it’s not about it’s it does not make us rich but It makes us enriched. And it’s important to know what we are signing up for.

Kayla Fratt 55:07

Yeah. And I think, you know, we talk all the time about testing things out on this court, you know, on this, this podcast, and you know, nothing has to be forever, you know, even like our fieldwork in Guatemala, when I was talking to my new PhD advisor, he’s the same advisor that of the student that I was working with there. And he was like, you know, would you be interested in trying to continue Ellen’s research or expand upon that for your own. And I was kind of like, you know, what, all the bugs, there were the worst bugs I’ve experienced in my entire life. And I’ve lived a lot of places with really bad bugs. I actually don’t think that’s where I want my main, my main field site to be for the next five to seven years.

Kayla Fratt 55:47

And, you know, that’s okay. I’m so glad we went, I would go back for another two week period of time. But, you know, and that’s, that doesn’t have anything to do with field. Well, inclusion. But you know, to some degree safety, you know, every bug bite, you get in the tropics, had some chance of carrying something horrifying with it. I had one tick, just healed now after about three months, and seems like nothing.

Sotra Chakrabarti 56:14

But yeah, I keep telling my students I’ve had malaria thrice. And, yeah. Yeah, it’s, it’s not, it’s, it’s tough to be out there. But it’s also as you said, it’s very important to actually know what you’re signing up for. So it’s important to feel comfortable to do something, rather than, like, just like, you know, not knowing what you’re getting into, as you can, as you very, very rightly said, that nothing is forever. Yeah, there’s always there’s always, like, if you feel uncomfortable, then just don’t do it. It’s not, it’s not worth it.

Kayla Fratt 56:57

And, and, you know, maybe on the safety note, you know, try to avoid getting into situations you can’t get yourself out of, or, you know, because, you know, emergencies can go bad really, really quickly. You know, I mean, this is a whole other topic that we don’t need to get into, but, you know, just thinking about, you know, encounters with elephants, you know, you can’t just walk away at that point. But if that’s, you know, that’s where we get into prevention, you know, there’s, there’s just so much to think about as far as the safety stuff goes, and the inclusion and how those fit together.

Kayla Fratt 57:34

You know, one last little anecdote to share before I ask if you have any more, you know, I was working with someone on one of the projects that I have been on, and actually this has happened more than once, where, you know, we agreed to use partner or in some cases use boyfriend as the local translation for someone who was in a gay relationship, instead of using the correct gendering and the translation, just because of, you know, for in various places that we’ve worked internationally, it’s not necessarily safe to, to say that you’re gay.

Kayla Fratt 58:07

And I think as students, it’s hard to figure out, you know, how and when and where you want to do research and how you can do that safely, and how you can do that in a way that feels good for you and your partner, because I’m sure most partners don’t really want to be erased that way, or misgendered that way. But it’s something that may come up particularly, and honestly, with the way things are in the US, it’s not even just an international thing right now.

Sotra Chakrabarti 58:32

Yeah, absolutely. No, I think I think it’s, it’s important to, I have, like a couple of my students, like a lot of my students are graduating in like, three days, and some of them want to continue with me to work with me in the future. And I keep, I’m like, Okay, let’s go have a feel of how it looks like. Like, you looked at the data and everything looks look, go find out how it looks like actually in the field. And then think about whether you want to commit or not, because you might just, it might either you would fall in love with it. Or it might be like, Oh, no, it’s it. This is not for me, and that’s totally fine. No judgement, you do something else, or you don’t. I, I will never be able to study probably over or really like chrome across places, because I am not a winter person or like a snow person. And I understand that. And that’s not going to work out for me.

Kayla Fratt 59:50

Yeah, so. Yeah. Yeah. I mean, that’s, that’s the same advice I got when I you know, I called a couple of folks as I got the job offer for the work that we did in Kenya and I was like, you know, a, you know, what do you know about this organization? And then would you recommend going and you know, what do I need to think about before I fly myself to Kenya because it was my first time doing something like that. And the advice I got over and over and over again from people was, go, but don’t sign yourself up for a two or three year contract without having been there for a while. And that’s what I did. You know, I was there for six and a half, seven weeks, and then I was ready to write a Fulbright to say that I was going to come back.

Kayla Fratt 1:00:24

But yeah, all right, well, stuff out where can people learn more about you or your lab stay up to date on all of your your comings and goings, and, you know, lions, fostering leopard cubs and all that amazing stuff. We’re just gonna leave that there. So people are motivated to go find you. I do have

Sotra Chakrabarti 1:00:44

I’m pretty much occasionally active on Twitter. And I am also I do also have a website. Do you want me to like, Would you be linking their website to –

Kayla Fratt 1:00:57

Yeah, we can just link it in the show notes. I think that would be, that would be perfect. Okay, yeah, you can just send it over to me.

Sotra Chakrabarti 1:01:07

Yeah. Yeah, I can definitely do that. I have. My email is connected to that website. So yeah, I’m pretty, quite responsible, responsive over emails, and I’m pretty much active on Twitter.

Kayla Fratt 1:01:19

Excellent. Well, and we’ll drop those links into the show notes and and for everyone at home. We hope that this podcast inspired you to get outside and be a canine conservationist in whatever way suits your passions and your skill set. You can find the show notes, transcripts, you know, merch sign up for courses, all that great stuff all over at k9conservationists.org And we’ll be back in your earbuds next week. Thank you!

Donate

Donate