We have been traveling for 56 hours. I am tired and stinky and buzzing with a nervous energy. Below the ferry deck in our laughably overloaded Ford Maverick, Barley is tucked between a cooler full of gear repair supplies and a pair of camp cots. His nest consists of two foam camp mattresses, two sleeping pads, and a Kenyan shuka as if he is our Prince and the Pea. Outside the ferry window, glassy sapphire waters slide by below a sky so bright it is almost white. The islands on either side of the boat bristle with dark conifers.

We will arrive at our final destination – Craig, Alaska – in four more hours. After what feels like eons of planning, we start fieldwork in three days. The past few months have been a frantic, flat-out sprint that brought me perilously close to burnout so early in my PhD. Juggling the care of two working dogs, preparing for fieldwork, keeping up with coursework, grantwriting, building friendships, navigating a complicated international romance, adjusting to a new town, moving out of the van I called home, and maintaining my beloved podcast and mentoring group has me frayed at best.

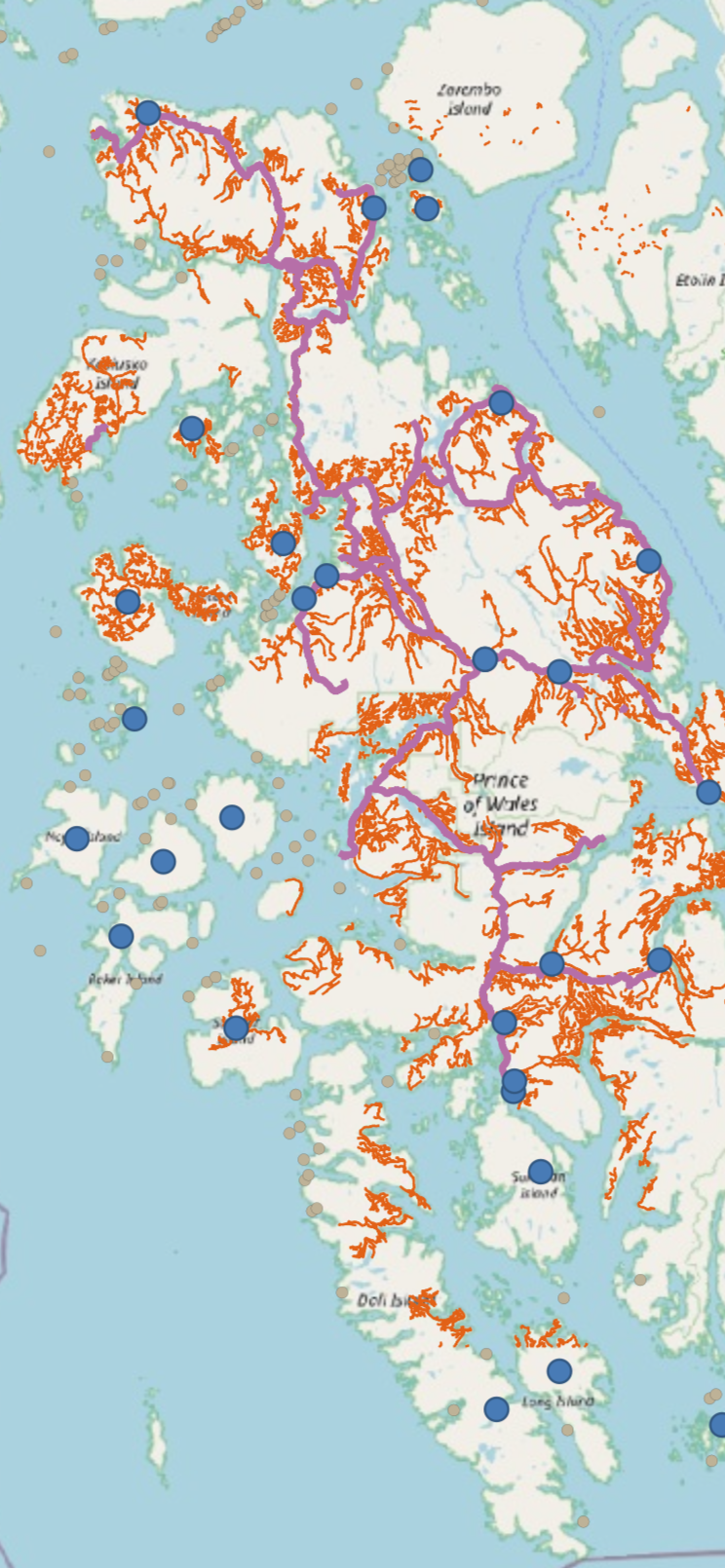

From the start, this project was almost too good to be true. When I won the prestigious National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship, I planned to study carnivore interactions and dry season resources in Kenya. For a variety of reasons, my advisor Dr. Taal Levi and I decided to pivot to building on existing projects examining the diet and behavior of wolves in coastal Alaska. The Alexander Archipelago wolf, Canis lupus ligoni, is a subspecies of wolf found in the farthest southeast reaches of Alaska. These coastal wolves move between the hundreds of small islands surrounding Prince of Wales, subsisting on a surf-and-turf diet. Alongside project partners at Alaska Department of Fish and Game, our goal is to estimate wolf occupancy on outlier islands, quantify the frequency of occurrence of prey species through wolf scat, and assess population connectivity between islands. And for that, we need scat.

That’s where Barley comes in. Arguably my most successful adult relationship, my derpy border collie is a top-notch conservation detection dog. His borderline unhealthy fixation on fetch and toys makes him an excellent coworker. He finds the scats, I throw his ball. The fact that he is really, really ridiculously good-looking is a bonus. I have shared my life with Barley since 2017, for every step of my career as a conservation detection dog trainer. He deserves an entire memoir. But today we will focus on the Alexander Archipelago wolf project. As I prepared for our fieldwork in Alaska, mentors warned me that even highly experienced detection dogs sometimes appear frightened of wolf scats. Frightened enough that “you can ruin a good dog by rushing this training.”

I devised a training plan that took into account the age and sex of the “donor wolves,” helped along by scat donations from Wolf Park in Indiana and the International Wolf Center in Minnesota. Over the past months, Barley often planted himself near the bin of training supplies around 3:30, insisting that our 4pm training session start on time. If I did not start search practice quickly enough, I got an earful of ferocious barks. When I finally whispered his search cue, he rocketed off, tail waving and nose canted upwind as tacks across the breeze. When he hit odor, his tail helicoptered and he “nose hooked” so sharply that his rear feet nearly overtook his forepaws, scrunching his back up like an inchworm. When he found the scat he folded into a down, pupils dilated into gaping holes as he awaited his beloved ball. Either my training plan worked, or he is exceptional, or the concerns were overblown. We will find out as we prepare more dogs for upcoming wolf research.

Other logistics for this project have not gone so smoothly. Originally, we planned to basecamp in Craig in my beloved Sprinter Saga. While on the outer islands, we would stay in a project partner’s gillnetter boat. But in January, I noticed a troubling shudder when Saga was idling at red lights. I took her in and got an injector replaced, which took until early March. As I waited to make a lefthand turn home from the mechanic, my stomach sank. The shudder was unchanged. We confirmed that the interior of the cylinder was worn smooth from the bad injector and that the engine would need to be replaced – at least a $10,000 prospect that we likely did not have time for even if we wanted to pour that money into a 17-year-old vehicle with 260,000 miles. Besides the emotional devastation of losing my first home, we were in a serious pinch for fieldwork.

We were able to arrange the rental of an Oregon State University motorpool vehicle, but they only had puny Ford Mavericks left for the dates we needed. Housing in Craig would be next to impossible to find this late in the game, as the tiny town gets flooded with seasonal workers. All of these logistics infiltrated my to-do list as I put finishing touches on my other pup Niffler’s training for an unrelated project and wrapped up my finals early so that I could head to an 80-hour Wilderness First Responder class. Taal and I brainstormed over email during my breaks in the class, finally settling on a huge canvas wall tent that came highly recommended by some elk-hunting contacts I had. Then I got another concerning call.

Gretchen Roffler from Alaska Department of Fish and Game is the mastermind behind this project. Her unplanned call could not be good, and I answered with a twinge of dread. She informed me that due to a variety of bureaucratic obstacles, our boat situation was up in the air. A few days later, it was confirmed that the gillnetter we had planned on was not an option. It took another tense week or two to identify a backup boat, which did not have sleeping capacity. We would be beach camping 4-6 days a week for 3.5 months, returning to another tent base camp for the remaining days, in an area that got twice as much annual rainfall as Seattle.

To be honest, I had a few weeks of serious doubt over the project. Though my field tech Toni is extremely competent and we are great friends, the project had abruptly gotten more challenging. I was not excited by the prospect of breaking down tents in the rain and managing bear safety in camp on top of the rest of our daily research duties. I had (and have) another major project in the works for my PhD, and perhaps these logistical challenges were a sign that I should pare down the projects and focus on the other.

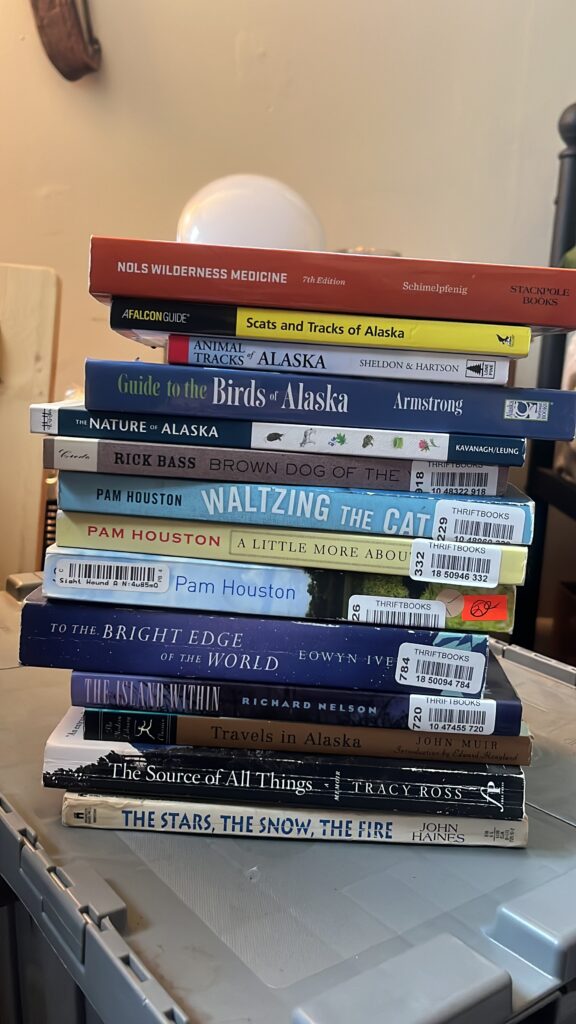

I waffled, but at some point decided that it was simply too late to back out. I was not sure enough that I did not want to give the Alaska project a shot, so I rededicated myself to gear preparations and training Barley. We had quite the expedition on our hands. Just after spring break, I ordered nearly $10,000 in research supplies and camping gear to ensure that we would be safe, effective, and comfortable for the seasons to come. Boxes piled high and I placed a box of snacks and drinks out for the delivery drivers to say, “Thank you, I’m sorry.”

Toni arrived to assist with preparations six days before our departure. We spent a full day setting up and testing our gear, another day making last-minute grocery and REI runs, and a third day printing data sheets and streamlining our sampling methodology plans. We sprawled across the yard and inventoried our gear, sorting it into clear bins with checklists taped to the lids. We picked up the little Maverick, stomachs sinking at the juxtaposition between its short bed and the mountain of gear. In the frenzied few days before departure, I recorded five podcast episodes while Toni diligently Tetris-ed the gear and carved out a nest for Barley. It all fit – barely. We got everything done but it felt like we had not taken a breath for days.

Finally it was departure day. I woke up before my alarm with a start. Did we need any paperwork for Barley to board the ferry? We did. Despite spending the past few years traveling overland across Central America, shepherding my dogs across more than a dozen international borders, I had somehow overlooked health certificates. It was 7am and our goal was to leave in an hour. We had a six hour drive to Bellingham, where a 36-hour ferry ride would start at 8pm. The next ferry was in a month. Missing the ferry was not really an option.

I was nauseous. I debated forging the health certificate, or hoping that they would not ask. As soon as my vet opened at 8am, I called and explained our situation. “We have a bit of an emergency, but all the pets are ok. We rather desperately need an appointment for a health certificate as early as possible.”

Amazingly, the team at Hello Vet was able to get me in at 9am. As long as we did not hit horrible traffic in Portland or Seattle, we would be ok. The vet team was ultra-efficient in the check, helping get us out the door quickly with a few tablets of Trazodone in hand to help Barley sleep and relax through the ferry ride. Then we drove north. And drove and drove. We arrived at the ferry dock with just 20 minutes to spare. The clerk let us know that the ferry was delayed by nearly 5 hours. At this point, this felt like a relief. We went for a four mile walk and ate poke and caught up with a friend who lives in the area.

When we boarded, I felt horribly guilty locking Barley in his truck-nest. Despite being an experienced traveler, Barley has never liked being left alone. Ferry rules allowed for a 15-minute potty break every six hours along the trip; I rarely leave Barley alone for more than four hours. I smooshed a Trazodone into a piece of sausage and told him to be good. Toni and I lugged our sleeping setups up several flights of stairs to the solarium. We claimed a sliver of floor and laid out our camp mattresses, sleeping pads, and books. I wished I could curl up in the truck with my best buddy. A few couples tucked into corners, a group of four young men goofed around on the lounge chairs, and three single men spaced out the best they could. Some were headed to Ketchikan, like us, but others had longer voyages to Juneau, Haines, and Skagway. The boat rocked us to sleep under bright yellow lights that never turned off.

The next morning, we woke to steady rain and thick fog that rolled over the jade colored trees. Gulls wheeled by and we mistook logs for dolphins amid the crumpled waves. For a crazy half-second, I thought a piece of driftwood was a sea turtle before remembering that we are not in Central America anymore. We laughed it off, and the glacial sea turtle is my new favorite crypid.

As Toni and I waited for over-easy eggs and hash browns in the ferry cafeteria, I noted that there seemed to be exactly two types of people on this ferry ride: elderly folks toting expensive cameras emerged from the cabins while young flannel- and Xtra-tuff-wearing dirtbags like us sprawled across the solarium. We met another traveler and spent the day doing a puzzle, conversation darting from AI to birding to childhood trauma to the intersections of ethics, politics, and dog training. Toni, always equipped with binoculars, spotted auklets and sea otters. We started to count the bald eagles and tally up boat-hours.

That day was punctuated by Barley’s short breaks from the truck. Despite the Trazodone, he was worried by the boat’s movement. While originally relieved to exit the truck, at the first sign of rolling his toes splayed and gripped the floor, and he tried to push into my knees. Barley has never been afraid of boats, planes, trains, or cars before. I am not sure exactly why this ride was different. I suspect that a bout of paralysis nearly a year ago that caused a new fear of slippery floors and unstable surfaces is to blame. He peed when asked and engaged in some training games to lift his spirits and move his body, but he was eager to return to the truck at the end of each visit. At least he found comfort in the truck; I was worried that he would be unwilling to hop back into the truck-nest after so many hours cooped up.

Ketchikan came into sight around 9am today. Barley barked in joy – or was it impatience? Discontent? – as I prepared his breakfast. We smashed gear into all available airspace, waved goodbye to our new friend, and drove to a patch of grass as fast as we could. Barley relieved himself immediately, then set to convincing us that it was time to visit the beach. We spent much of the day walking Barley around town, soaking up the sun and relishing in solid ground. Before loading onto our next ferry, I shared a smoked salmon bagel with Barley as an apology. We’re almost there, buddy.

We love to hear from you. Please share this post and ask us questions in the comments if you enjoyed this piece. It helps us know you’re there and feel inspired to continue sharing stories.